I signed up for The Rift, a 125-Mile gravel race through the highlands of Iceland, in what feels like a different time. In December 2019, I was gearing up for a season on a Specialized all-women's gravel team, promoting my gravel race, Ruta del Jefe; and directing the new Radical Adventure Riders gravel team and gravel squad. 2020 would be a year of gravel events, and then the pandemic hit, and my priorities shifted.

I withdrew from most of the races I registered for except for a couple; The Rift and SBT GRVL. I kept my registration for SBT GRVL because Adam, my Dad, and so many of my gravel pals are signed up. Located in Steamboat Springs, Colorado the event will double as a reunion with family and friends from all over the country.

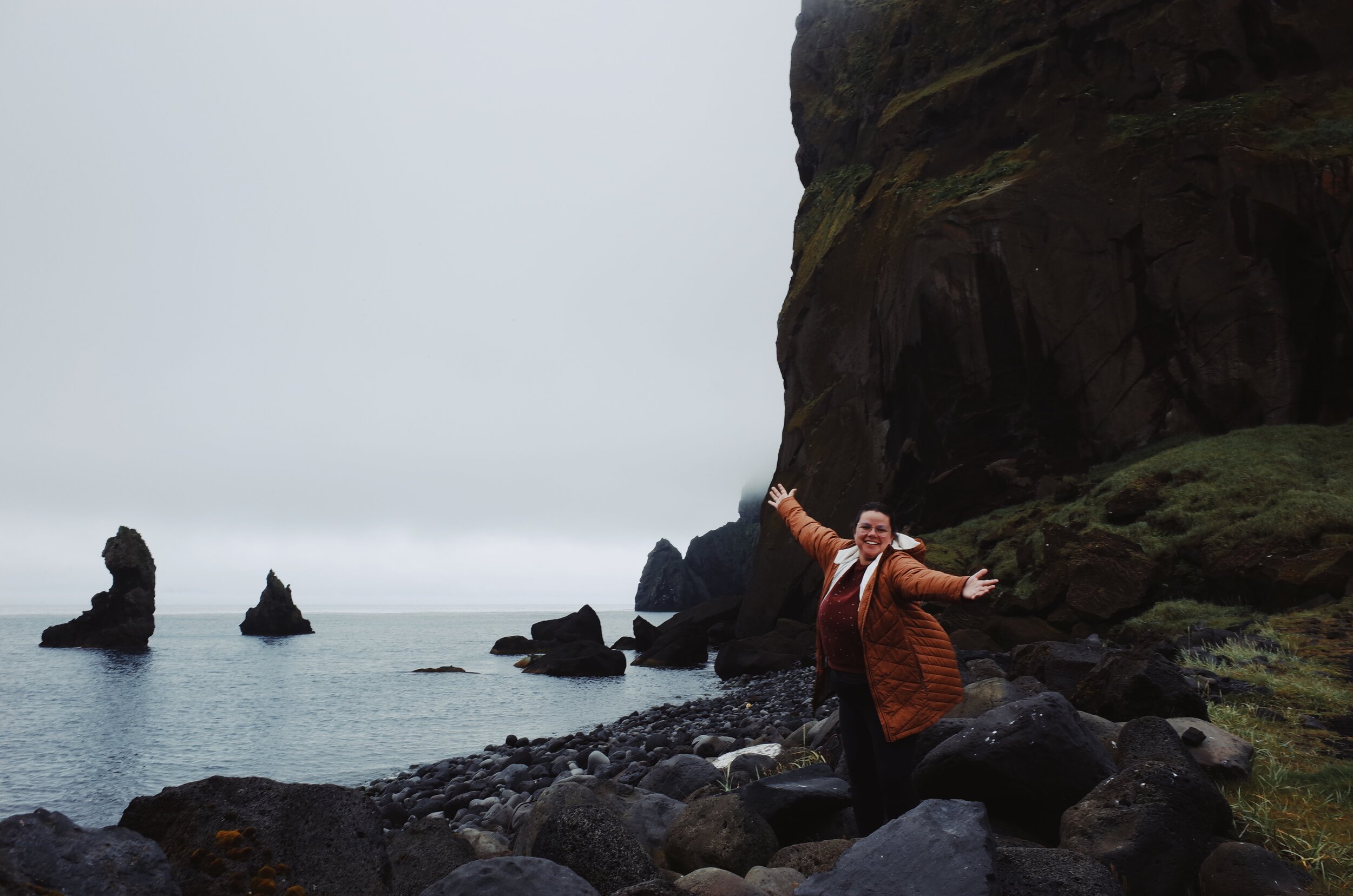

I kept my Rift registration because I was most intrigued by the location and route. Traveling to Iceland for a gravel race seemed like the perfect opportunity to get a taste of Iceland's landscape, gravel, and weather conditions to see if I could ever bike tour there.

After more than a year without traveling, I decided to book my ticket to Iceland even though I did not have companion to join me yet. I planted the seed with some family and friends, and soon enough, my sister Margaret signed up for the trip. Traveling to Iceland with Margaret, who is two years younger than me and lives in Cincinnati, Ohio, would be a truly unique experience for both of us; it would be our first time traveling together and our first time in Iceland.

Two-and-a-half weeks after finishing the Tour Divide, I heaved all my heavy bike baggage on the plane to Iceland. I was surprised to realize that packing to fly for a five-day trip and a one-day gravel race required more gear than packing to fly for a one-month bike tour. After all, I would be traveling differently than I usually do on this trip. Typically, I only experience places I travel to by bicycle, but since Margaret is not the bike fanatic I am (yet), we would be traveling like most other tourists in Iceland; by car and by foot.

Margaret and I met in the Denver airport after nearly two years without seeing each other. When we reunited, it only felt like yesterday that we were sharing a bedroom as kids, an apartment in college, and more recently, sitting in my parents' kitchen chatting and laughing with other family members during one of our brief reunions. We effortlessly picked up right where we left off.

We arrived at the Keflavik airport outside of Reykjavik at around six in the morning. After retrieving our rental car, we refreshed our manual driving skills by transporting ourselves without stalling to the notorious nearby hot spring resort, The Blue Lagoon. At the Blue Lagoon, we soaked our weary travel muscles in a steaming hot aqua lagoon as people from all over the world slowly walked, whispered and floated; faces covered in mud masks and hands filled with a complimentary cocktail or juice. We marveled at the oddity of it all, shamelessly partook in the whole experience, and got a refreshing post-travel rest and shower before making our way to see the recently erupted Fagradalsfjall volcano.

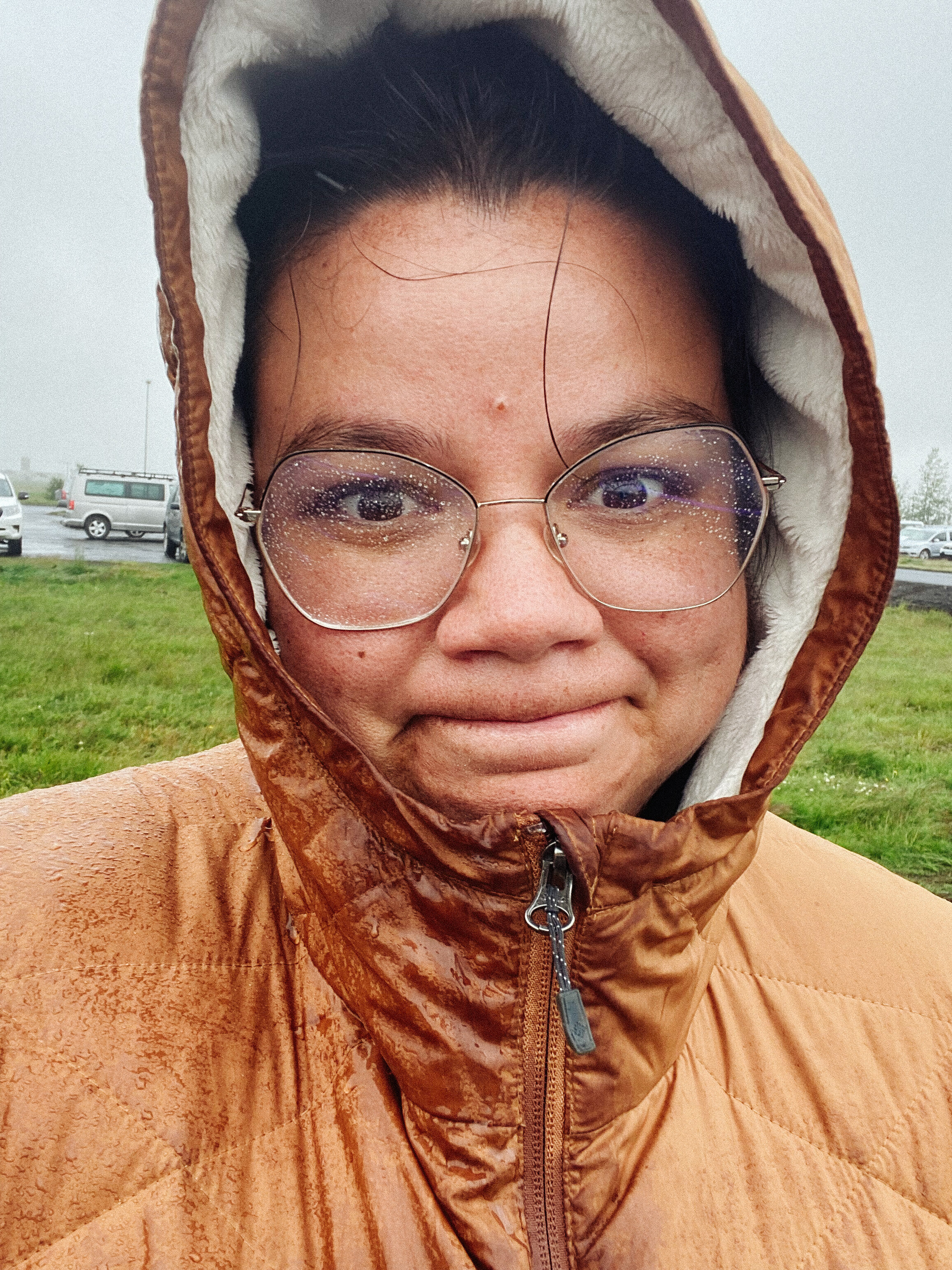

I closely followed photographer Chris Burkart's images and videos from when the Fagradalsfjall erupted in April, so naturally, I imagined that we would be able to hike to see molten red lava billowing from a volcano. Not so. The only indication that we had arrived at the volcano was Google Maps and hundreds of cars parked in fields on either side of the road; the fog was so dense we could only see 200 yards in the distance. However, we weren't deterred and hiked our way up to the bottom of a massive lava field. As we wandered further and further along the lava field, we slowly came to terms with the true scale of this eruption and how far the lava had traveled from its source in a few short months—miles. This day was not our day to see a volcano, but the lava fields were mesmerizing.

The first time I rode my bike in Iceland was the second day we were there. Having managed our jet leg so well the first day, we ruined it by sleeping until 10:00 a.m. the following day. Waking as if we had squandered half the day, we rushed to make a plan to maximize what was left. We decided to take the ferry to Vestmannaeyjar to see the largest puffin colony in the world. The goal was to meet to catch the 1:15 ferry. I would ride to the ferry port, and Margaret would drive. By the time we decided on the plan, it was 11:30, so I rushed myself ready for a 25-mile bike ride that would include dirt and paved roads. Looking back, I don't know what I was thinking when I thought I could complete this ride in an hour-and-a-half; perhaps it was the jet lag, or the 24-clocks, that little nibble of an edible, or just my perception that this part of Iceland was easy.

Within five minutes of riding in the wind, rain, and on the washboard dirt roads, I realized that I would need to engage in a flat-out time trial to meet Margaret at the ferry in time. I was riding as hard and fast as I could, but I knew there was no way I was going to make it in time. I thought that if I could get to the road that goes directly to the ferry, I would have the opportunity to intersect Margaret or hitch-hike the rest of the way with another ferry-goer. When I finally reached the road, there were so few cars passing that I could not commit to stopping to hitch-hike, so I kept pedaling as hard as I could hoping there was a chance that the ferry was running late but also stuck my out my thumb when a car passed by. Of course, no one picked me up until Margaret rolled up behind me. She was running late too. We made it to the ferry in time but exhausted from the stress of rushing, we asked the ferry attendant to switch to a later ferry. Thankfully they accommodated us, so we could slow down, catch our breathe and check out some nearby waterfalls. This day was by far the most fun day of our trip. We ended up seizing the day and saw it all, even the puffins, despite the continuing wind, rain, and fog.

The Rift

The forecasts for race day were temperatures in the low 50's, steady rain, and constant wind. Figuring out the right clothing combination to keep me from overheating and from getting hypothermia during a 125-mile ride was the one thing that kept me up the night before the race. The dilemma was whether or not to wear leg warmers. The temperatures were undoubtedly cold enough for leg warmers. Still, my experience in similar wet conditions on the Tour Divide was that wet leg warmers on my knees are a bother, and I wound up riding all of the wet, cold days in New Mexico without any knee anything on my knees. My instinct was to go without, and so that was my plan. However, when I showed up at the start of the race and saw all the other riders with covered knees, I abandoned my plan and put the leg warmers on. Thankfully, Margaret was there to provide an objective and sisterly perspective by reminding me to follow my gut. At the last minute, I took the leg warmers off and toed the line.

I have to admit, as I lined up at the start of The Rift among the likes of the accomplished Sarah Sturm; the women's road national champion, Lauren Stevens; and retired cyclocross champion, Meredith Miller; I could not help but wonder what the hell was I doing there. I looked back to see if I could shimmy my way backward through the riders packed like sardines but ultimately succumbed to my position and fate.

Within the first 10-miles of the race, everything in my body protested the speed and exertion I was attempting to maintain. As it turns out, riding between 100 and 150 miles a day for 21 days is not ideal training for the high intensity of a single-day gravel race, or at least the start of one. I felt no benefit from the four interval rides I managed to squeeze in during the two weeks between the Tour Divide and The Rift.

After spending another 10-miles or so getting passed by what felt like the entire field, I swallowed some humble pie and shifted my focus to settling in and just riding the ride as if it was just another day on the Tour Divide. For the first time, I took in my surroundings. Clouds of fog laid eerily over an otherworldly landscape. Black roads of lava rocks and sand rolled steeply over hills and through deep rivers of glacial melt. Occasionally the fog would clear to reveal the surrounding cone-shaped mountains highlighted in neon moss. Rarely have I ever been in such awe.

Thankfully, my clothing choice panned out— wearing what I had worn during my Tour Divide ride: shorts, a merino t-shirt, and a rain jacket. I was perfectly content with what I was wearing and did not have to stop to delayer or layer up once.

Jaimie Lusk showed up right around the time I was pulling myself out of the hole I buried myself in. Hailing from Oregon, Jaimie was riding a steady pace and even offered that we could ride together. Flattered but not hopeful, I picked up my pace to hang and chat with her for a little while. That little pick me up may have been all that I needed, for, in a few miles, I started feeling a lot better. I settled into a faster rhythm, left Jaimie behind, and eventually caught a group of riders. This group included Meredith Miller, the retired professional cyclocross racer.

When I was racing cyclocross in Ohio (over ten years ago), I watched Meredith in admiration as she dominated the UCI3 races in my local cyclocross series. The Rift course was probably the most cyclocross style gravel course I had ever ridden-- steep hike-a-bike hills, technical off-camber, rutted descents, sandpits, and river crossings. I thought it was pretty cool to be riding such a course on the wheel of a cyclocross legend and marveled at Merediths' grace on the lines she chose.

The first time I stopped on course was at the halfway checkpoint and aid station to fill my bottles, stuff my face with some potato chips, drink half of a Pepsi and grab some stroop waffles to-go. I thought I was moving through the station pretty fast until Jaimie showed up after me, hopped off her bike, refueled, and was back on her bike before me. Jaimie was no longer giving off her friendly and chatty vibes. Instead, she seemed focused and determined at the aid station, which signaled that she was racing and that maybe I should pick up my game a little. So, I hopped back on my bike and pedaled to keep Jaimie within reach.

In 5-miles, we would have the opportunity to stop again to put on some dry socks and clothes at another aid station. I couldn't decide whether to waste time stopping or to keep going, so I decided to leave it up to Jaimie, who was still in front of me; if she stopped, I would stop. If she kept going, I would do the same. As we approached the dry-clothes zone, I watched ahead as most riders rode through a river that was calf-deep and stop at the station to swap their socks. Jaimie did not stop. It was on. I pedaled past the station and eventually caught up to Jaimie's wheel and said with some sarcasm, "no dry socks for us!" to which she replied, "It wouldn't make any difference." She was right. Had we swapped our socks, they would be soaked from the rain in minutes. Jaimie's determination motivated me again and pushed me into another good rhythm. I left Jamie behind again, this time though it felt like it was for good.

I kept a steady pace throughout the second half of the course and only stopped briefly at one other checkpoint. Battling a headwind for the second half of the course, I rode solo and with small groups while they lasted. A solid 20-mile section of severe washboard roads took my neck and back from feeling bad to terrible. Every bump was torture. Even though I was limping my way to the finish line, I was feeling pretty content, considering I managed to hold off Jaimie and Meredith. This feeling didn't last long, though. Out of nowhere, Jaimie, drafting off a wheel of a tall Viking-like fellow, blew past me, going twice my speed.

I was stunned and faced with the dilemma; to chase or not to chase. In races in the past, this is the point where I typically roll over and give up. Usually, this happens well before the last 50-miles, so I can somewhat justify it, but this was with only 10-miles to go. I had to try. Digging deep, I jumped on Jaimie's wheel. I knew that if I could hang on to this frantic pace through the dirt, I might have a chance of prevailing on the pavement. I hung on with all that I could. When we reached the pavement, our group of three formed a swift-moving echelon through the wind during which I was able to recover some of my energy. I was conscious of how long I worked and how long I rested.

Eventually, the echelon started losing its momentum, and Jaimie took off in an attack. I chased after her and was back on her wheel within a minute. We rode side by side for a bit until Jaimie admitted, "that's all I got." I was shocked. I had worked this hard to keep up for "that's all I got." Then, sensing that I was through too, Jaimie offered that we make it easy on each other and ride it in. At this point, I felt like I was committed to racing, and I needed to see the effort through. It didn't matter what place we were racing for, it was a game, and there is nothing quite like an excellent game to bring out my competitive side. As we approached the final climb, I stood on my pedals and hammered over the top. On the other side, I dropped into my aero bars and did not look back. Seeing double, I crossed the finish line to see Margaret's smiling face despite looking like she had been waiting in the rain for hours. The race was finally over.

If Jaimie wasn’t out on the course to push me, I would have had a very different race. Having other women to race around has been a massive motivator to push myself in a way I never would otherwise. Imagine if there were as many women as men out on these gravel race courses. What an experience that would be!

When I went to Iceland, many folks asked me if it was a job requirement for me to participate and perform in gravel races. While gravel racing is definitely trending, and my sponsors certainly appreciate the occasional participation, I am not required to do gravel races. Instead, I have the privilege to do any type of riding I want to do. Sometimes, that is doing the Tour Divide, bike touring in another country, riding my mountain bike in the San Juan Mountains, or doing route research in Southern Arizona. Sometimes, that is signing up for gravel races. You don't have to consider yourself a racer to sign up for gravel races. I sign up for gravel races to challenge myself outside of my comfort zones, in new environments, prove to myself that I am strong and capable, and to learn lessons that will help me improve as a cyclist. It doesn't really matter where I end up. All that matters is that I do my best while pushing my limits. The Rift was an opportunity to take on such a challenge in a new place, bookended with a memorable vacation with my sister Margaret. And yes, I would love to return to Iceland someday for a hut-to-hut style bike tour to ensure I had a place to dry out every night.