If you are curious about how I planned my resupply points along the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route for the Tour Divide, look no further. Prior to the ride I spent hours cross referencing resupply resources for the GDMBR and importing them onto Ride with GPS, my go to navigation and routing platform. I also added some POI’s that I am particularly interested in such as summits, creek crossings, dispensaries, and laundromats. After using this map throughout my ride I have got to say that it is pretty darn accurate but keep in mind that water levels could change every/.throughout the year of course and some businesses may change their opening hours. The video above outlines how I researched the POI’s and plan my resupplies along the route. I do this before every ride I go on. Now, with this process outlined, you can too! Lastly, I have divided the entire route into six different route segments making them a slightly more digestible file to view, download and upload. Check those out in my Great Divide Classic Collection.

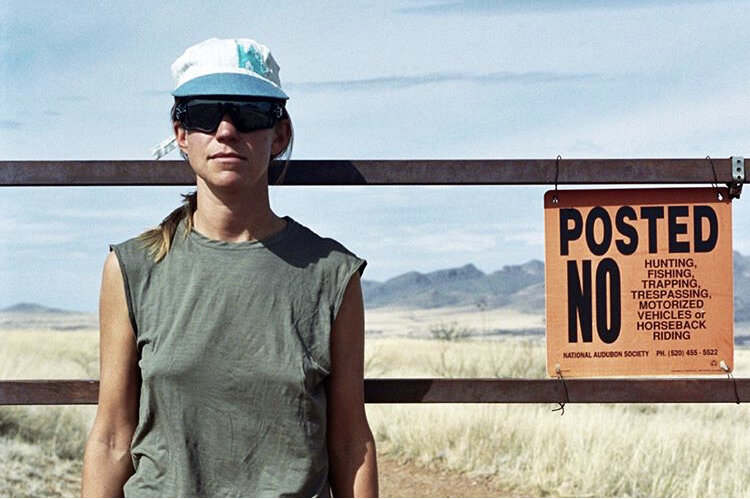

Photo by Todd Gillman

How To Follow My Ride on the Tour Divide/Great Divide Classic

My race begins at noon MT on June 11. You can follow the race and where I stack up against the rest of the field (look for my initials, SS) at this link: http://trackleaders.com/tourdivide21

If you would just like to follow my dot on a map, you can do so at share.garmin.com/sarahjswallow

Jorja Creighton will manage my Instagram account and provide entertaining content and updates that I send to her throughout the race. Follow along on at https://www.instagram.com/sarahjswallow/

To donate to my Gofundme campaign to increase accessible outdoor opportunities for teen and pre-teen girls, click here: https://charity.gofundme.com/o/en/campaign/sarah-swallow-tour-divide

If you would like to check out the route I am following click here: https://ridewithgps.com/routes/36276801

See you on the other side!

My 2021 Tour Divide / Great Divide Classic Detailed Packlist

In one week, I will be starting one of the most intimidating rides of my life. I would be riding the Tour Divide Mountain Bike Race in any other year, but because Canada is closed due to Covid, this year's event is called the Great Divide Classic. It's essentially the same, less than 250-miles of riding along the Canadian Rockies and follows the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route by Adventure Cycling Association. All totaled, I am looking down the road at a 2,500-mile ride with 150,800 ft of elevation gain from the border with Canada to the border with Mexico along the Continental Divide on dirt roads, single-track, and pavement.

My Philosophy

My bikepacking set-up 2018-2020. Photo by Jorja Creighton.

Preparing my equipment for such a journey has felt like learning how to bikepack all over again. Why is that? I believe that it is because when I am touring and only riding 35-50 miles per day, it doesn't quite matter if I bring my sandals, a super deluxe tent palace, town clothes, swimsuit, snorkel/mask, a 5-star cooking set-up, etc. (you get the idea). When there are anywhere between 10-14 hours of daylight, and I am going only 35-50 miles, I have all day to go as slow as I want to get to where I am going.

In contrast, the Tour Divide or the Great Divide Classic (whatever we want to call it) is a race. Just to be considered still in the race, I must maintain over 95-miles per day every day. My goal is to ride 100-miles per day and finish the route before I need to abandon the ride, which, at a minimum, will require that I ride 85-miles per day every day. So, for the first time in seven years, and when I started bike-touring, I have had to re-evaluate every little gear decision I make to feel like I can ride that amount of distance loaded with everything I need day after day. If I pack too much, my bike will be cumbersome to ride, hard to pedal up mountains, and pretty uncomfortable. If I pack too little, I could be equally miserable. I could not be prepared enough for the elements; rain, hail, cold nights, hiking through snow. I could be sleep-deprived and find the experience unbearable, leading me to abandon the course due to not having fun or being unhappy.

My gear and bike set-up for the Tour Divide/Great Divide Classic is my interpretation of a healthy balance between an efficient race set-up and a comfortable home on wheels for about a month. I believe that this set-up is light enough for me to travel the distances I want to travel while still feeling like a human. I'd go so far as to call this a luxurious race set-up. After all, I am a lifestyle athlete for a reason, not a racer. Only time will tell if these decisions, speculations, interpretations, and financial investments pan out to my benefit.

Itemized below is a detailed breakdown of my bike set-up for the Tour Divide/Great Divide Classic in 2021. The race begins on June 11. You can follow the race on http://trackleaders.com/tourdivide21. If you find this breakdown of value please consider donating to my Gofundme campaign to increase accessible outdoor opportunities to teen and pre-teen girls through The Cairn Project. Any amount donated gets me closer to reaching my fundraising goal of $8,000. Click here to donate.

Bike Specifications

This is my bike for the Tour Divide 2021

I am riding a Specialized Epic Hardtail Pro mountain bike with the stock Rockshox SID 100mm travel fork and 29" Roval Control Carbon wheels. The front wheel is laced to a SON Dynamo hub which fuels my Sinewave Cycles Beacon headlight. With the help of many friends and mechanics, I have modified this bike with Enve 48mm Gravel drop bars and Specialized aero bars. I also converted the drivetrain to a SRAM AXS electronic shifting system, which I find incredibly reliable and efficient but requires that I swap out and charge a small battery every 400-miles or so. The gear ratio I am running is an 11 x 50 tooth cassette with a 34 tooth front chainring. I may spin out on some faster pavement sections, but my knees will be happy on the climbs. The tires I have chosen for this ride are Specialized Ground Control tires which may be on the nobbier side compared to most, but it's a tire I have run for many years and I trust on all terrain.

I am using a Brooks Cambium C17 saddle; a zero offset seat post, and a 60mm, -20 degree stem, to accommodate my bike fit.

Bag Overview

My front bag system is made by Porcelain Rocket. It includes a minimal harness, a Dyneema stuff sack, and an outer pouch. I used this system on the TAT six years ago, and I have yet to find a better alternative. Inside the stuff sack, I keep my shelter and sleep system. Inside the outer pouch, I store my eating utensils, backstock of electrolytes, mushroom coffee, protein powder, THC and CBD edibles, and my water filter. I try to keep this bag filled with lighter stuff to avoid adding more weight to the handlebars.

I am using a custom frame bag by Rogue Panda Designs out of Flagstaff, Arizona, which includes an elastic zipper that allows me to stuff it to the gills and still be able to close it. In the large main pocket of my frame bag, I am carrying my tool kit, bear spray, and the majority of my food. In the frame bag's smaller side pocket, I store baby wipes, a clear pair of Ombraz sunglasses, and my wallet.

The seat bag I am using is a Gearjammer bag by the wonderful folks of Oveja Negra in Salida, Colorado. My Gearjammer stores my spare tube, toiletries, sleep clothes, a pair of shorts with a chamois, puffy jacket, and rain jacket. I have also added a bungee cord to the Gearjammer to hold my Thermarest pad.

My cockpit bags include a Mag Tank 2000 and Jerican by Revalate Designs (Anchorage, AK), an Eco-pack Snack Hole by Swift Industries (Seattle, WA), and a Chuckbucket by Oveja Negra. I store my multi-tool, headlight, sunscreen, and bug spray in the Jerrycan. Inside the Mag Tank 2000, I keep my point-and-shoot camera, phone, headphones, and additional snacks. The Chuckbucket holds my battery pack, electronic accessories, and a bug head net. There is room for more too. Lastly, the Eco-pack Snack Hole stores a 26 oz water bottle.

Holding my 64 oz Kleen Kanteen is a Manything Cage by King Cage (Durango, CO), mounted to my carbon down tube using King Cage universal support bolts.

The Nitty-Gritty Details

Tool Kit

Leyzne Micro Floor Drive

Blackburn Wayside Multi-Tool

Dynaplug with extra plugs

Wolf Tooth Pack Pliers with two 12-speed chain links

Leatherman Squirt

Silco Valve Extender

Pedro Tire Lever

2 x 2032 batteries (for my shifters)

Presta valve adapter

Finish Line Dry Lube (inside a wet-lube bottle)

Zip ties

4mm, 5mm, and 6mm spare bolts

Derailleur hanger

Superglue

Tire boot

Patches

Extra set of brake pads

Electronics

Garmin 1040 Plus

Garmin Inreach Mini

iPhone

15,000 mAmp Anker Battery Pack

Ricoh GRII Camera

Princeton Tech Headlight

Energizer 2 x USB wall port

SRAM Etap battery charger

Spare SRAM Etap Battery

2 x micro USB cables

camera cable

iPhone cable

Headphones

SD Card Reader for iPhone

Not pictured: Sinewave Cycles Beacon Headlight, Light and Motion Taillight

Toiletries

Buzz Away Bug Spray

Tom's Toothpaste

Tweezers

Ibuprofen

Benadryl

Dr. Banners Soap

Toothbrush

Chapstick

Dermotone Lip Protection

Aloe Up Sunscreen

Earplugs

Tea Tree Oil

Floss

Spare Hair Tie

Honest Wipes

Bandaids

Not pictured: Deva cup

Eating Utensils

Snow peak Spork

Opinel No. 7 Knife

Handkerchief

Can opener

Water

64oz Kleen Kanten

26oz Purist Waterbottle

3 Liter Kataden Befree Gravity Filter

Aquatablets

Sleep System

Mountain Laurel Designs FKT Bivy

Western Mountaineering Summerlite Sleeping Bag (32 degrees)

Klymit Inertia Ozone Sleeping Pad

Thermarest Z-Rest

Western Mountaineering Flash Down Booties

Bug head net

Clothing

Ombraz Dolomite Sunglasses

Ombraz Classic Clear Blue-blocker Glasses

Rapha Merino T-Shirt

Rapha Randonne Shorts

Ridge Merino Briefs

Branwyn Merino Bra

Bandana

Randy Joe Fab Linen Cap

Merino leggings

Merino long-sleeve shirt

Topo Designs Wool Hat

Rapha Women's Classic Shorts

Rapha Explore Hooded Goretex Rain Jacket

Rapha Explore Down Jacket

Showers Pass Rain Pants

Showers Pass Merino Socks

Showers Pass Merino Gloves

Specialized Prevail II Helmet

Not Pictured: Specialized Rime 2.0 Mountain Bike Shoes

Backstock

Four Sigmatic Protein Powder

Four Sigmatic Coffee Latte Mix

Ultima Electrolyte Powder

Ripple 1:1 CDB/THC Powder

Wanna THC Gummies

RonsBikes Puff Pouch

2021 Tour Divide Packlist Video

Update: My Gofundme Campagin for the Cairn Project

Thanks to so many of your generous donations, I am just $500 short of my goal of $5,000 to increase accessible outdoor opportunities for teen and pre-teen girls through The Cairn Project, and I haven't even started the ride yet! The support and tributes to the women in your life fill my soul with gratitude and inspiration—what an incredible way to kick off my journey next week.

I'd love to keep this momentum up, so I am increasing my goal to $8,000. $8,000 will fund nearly two grants for two different outdoor programs for young women and girls. If you have the means, please consider donating any amount to this effort. Click here to donate. Thank you!

To learn more about why I am fundraising for increased outdoor access for young women and girls, I invite you to read my personal story, How Finding what I Loved to do Outdoors Changed my Life Trajectory.

How I Am Preparing for The Tour Divide

I committed to doing the Tour Divide on March 7, 2021. Before my decision, it was in the back of my mind to consider because my friend, Arya, had committed to doing it. With Covid still in the air, my perspective of traveling in poorer countries in flux, and Adam, my primary adventure companion in school full-time, it finally seemed like an optimal time to take on the Tour Divide. As I write this, I am wrapping up only my fourth week of focused physical and mental preparation. I spent the first month converting my bike, figuring out most of my gear choices, wrapping up projects at the Ranch, saying goodbye to my Arizona friends, moving back to Durango, and taking a week-long Wilderness First Responders course. As I look back to my free-as-a-bird lifestyle down at the Research Ranch this winter, my only regret is that I had not used more of my time there to start this whole preparation process then. But I don't regret having had the time to replenish myself, for, without it, I likely would not have had the capacity to consider taking on such a significant challenge.

The Tour Divide will likely start at the U.S. Canada border this year in Roseville, Montana, which means instead of being a 2,667-mile course with 152,000 ft of climbing, the route I'll be riding will be 2,400-miles with 133,000 ft of climbing. Having done the Canada section of the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (GDMBR) twice in the last five years, I like the idea of getting closer to places I have not yet ridden, sooner rather than later. Don't get me wrong. I am also counting every single mile and foot of elevation gain to help me finish before my allotted time frame of thirty-two days. I have created this specific allotment because that is the amount of time I feel like I can commit to this goal. I am registered for The Rift in Iceland on July 24, a 140-mile single-day gravel race. I will be traveling there with my sister, Margaret, the week before the race. It will be our first time getting to travel together, and I cannot wait. Thirty-two days allows me to have a week of recovery between wrapping up the Tour Divide and traveling to Iceland. It's not much time to recover and also train at an anaerobic level to be competitive at The Rift. While I would always like to do the best that I can and see where I end up, I am more motivated to do The Rift because the route looks so cool, and I might even get to see an active volcano (a first for me).

Let's get mathematical for a second. 2,400-miles with 133,000 ft over thirty-two days is an average of 75-miles per day and 4,200 ft of elevation gain on a loaded bicycle. That is a limit that feels very doable for me at this point in my preparation. I will be pushing myself toward finishing in twenty-four days, which means I'll need to average riding 100-miles and 5,550 ft of elevation gain per day on a loaded bicycle. This twenty-four-day goal feels a bit more intimidating and the reason why I do feel the need to "train" as much as my psyche typically resists such a construct.

My Suffering Is Nothing Special

My first training ride was almost my last and the end to this whole lofty Tour Divide idea. I had traveled out to Paradox Valley to mess around and micro-dose on mountain bikes in the desert with the legendary Max Cooper and his Colorado gang for two days. I had only been home in Durango for a total of 4-days since moving from Arizona and doing my WFR course. Still, I pushed through the desire to be a homebody to venture and spend time with these friends since the opportunities have been few, yet are always worth the while. I also thought that it would be a great idea to ride home solo from this hang as a good training ride for the Tour Divide, so that's what I did. As my buds hung at camp on our last day, I put my Stumpjumper on the bike rack and pulled down my Epic touring bike, packed it up with more than enough food for two days and enough water to get me to my water cash. I then rolled away from camp on my own to see if I could "handle it."

Twenty miles into my ride that day, I had reached the most significant question mark on my entire route. I was looking for some trail that would take me from the Paradox Valley in Bedrock up 2,000 ft to Davis Mesa. Max had heard of this trail. When I told him I planned to take it, he relayed a rancher story who took his cattle down the trail one cold winter day. The trial was iced over in some sections; 12-cows slipped over the exposed trail edge and landed on an isolated ledge. As Max told the story, there was no possible way to rescue the cows, and there they stayed and eventually starved and died. I don't know why this story didn't set off alarm bells for me; perhaps it's because I was putting a little too much faith in the new RidewithGPS heat map feature, which highlights ways cyclists (and possibly hikers?) have logged trips before. Someone has done it, which means I can probably do it too, I thought.

When I reached my cue to turn onto the trail, I did not see a track, I saw a ditch. "Perhaps the trail is a little further, and I didn't route to the right access point," I thought, so I carried on. I was definitely on a trail, but this was not a mountain bike-worthy single-track trail, as evident by the loose and abundant rocks askew. I carried on further, pushing my bike up-up-and-up. "This trail has got to get better eventually, and it won't last forever." Yet, the higher I got on the trail, the more I lifted my bike over-head and over boulders, the steeper and more exposed the path became. When I approached evidence of a rock slide across the trail, I realized I had gotten myself into a serious pickle.

I thought of the twelve cows and looked around. "Where could they (or I if it came to it) possibly land?" I had spent so much time coming this far on the trail, and my stubbornness persisted. I felt like I could see the top, and if I could get through this next series of sections safely, I could make it. So, I slowed things down, and I put on my helmet. I test walked across the slide to see if the footing was secure. It seemed to be. I drank some water and proceeded to remove all of the bags from my bike. I first took my bike across the slide with the extreme focus to not fumble my steps and then walked back to do the same with my bike bags. I continued this pattern for another half-mile and 800 ft of elevation gain until the trail finally leveled on top of the mesa.

That evening I proceeded to ride another 40 more miles into the dark to my water cache. When I reached my cache, I was so tired that I camped in the closest spot I could find secluded from the road. I then fell asleep three times while preparing my dinner and eventually woke around 1 a.m. to finish it up. In the morning, I realized that not only was this spot on a hill but cow and deer dung surrounded it. But, at the time, I was in high spirits for what I had accomplished the day prior. If only I could carry that energy through the 35-mph headwind forecasted as I climb to the Rocky Mountains that day. Not so. Within 3-hours of my ride, I was so physically uncomfortable, miserable, and exhausted that I texted Adam in tears. "Hey babe, I'm struggling out here. The headwinds uphill are killing me, and my body feels wrecked from yesterday. It's making me not want to do the Tour Divide." To which he offered to pick me up. I was still quite far away from our original meeting point and had no option to keep pedaling as far as I could so as to cut down the amount of time and distance Adam would have to travel, but I took him up on his offer, and we planned to meet in a few hours.

As we drove the final 30-miles of the ride, I could not and would not finish; I processed what had gone wrong in my failed first training ride and questioned whether or not I was even cut out to do a ride like the Tour Divide. Adam encouraged me not to make any drastic decisions for a few days and shared the meaning of a mantra which has stuck with me ever since. "My suffering is nothing special." On the Tour Divide, I won't be the only rider suffering in a headwind uphill. Also, when it comes to suffering, there are so many more people around the world actually and legitimately suffering, especially right now. What a privilege it is to be able to choose to suffer in such a small way.

Within a few days of being home again, I was invited on a small group tour in the Dolores Canyon with a crew of folks I had never met before. The Dolores Canyon Tour seemed like a fun opportunity for redemption from the Paradox Valley tour, so I agreed to go. Before the trip, I took my packed bike from my solo tour the week before and shed it down to the necessities. I got rid of the front panniers, used a lighter and smaller bag upfront, got rid of my cooking set-up, and only carried enough food for 2-days. I had been bothered by how heavy my bike was on the last tour, how much extra food I had brought, the extra water I had carried, and how much my bike bags felt like they dragged through the wind.

Riding with a fun motley crew of strangers through the dramatic red sandstone walls of the Dolores Canyon and diving in its deep swimming holes reminded me of my love for living on the bike. I felt strength and rhythm in my body and legs again. I was satisfied by how comfortable my more minimal set-up was. This trip was also a reminder that my "failed" Paradox Tour was merely an essential step in my preparation for the Tour Divide. It was simply an uncomfortable moment in time, like those bound to occur on tour, which will inevitably pass into times like the Dolores Canyon Tour.

Training Philosophy

I came away from the Dolores Canyon tour with a renewed focus on my original goal. But, 100-miles per day every day for twenty-four days is still quite a challenge, and I needed to figure out how to prepare my body for that to avoid the level of discomfort I felt on the Paradox Tour. To keep these anxieties at bay, I have done two major things: I scheduled a bike fit, and with Adam's coaching, constructed a basic daily training plan that seems attainable for how much time I have. The bicycle fit ensures I am in a position that will limit my chances of injury while also being comfortable and optimal to ride all day, every day. The loose training plan primarily serves as a guide keeping me accountable for riding five days a week. I've been taking two days off each week. I typically spend my weekends which are supposed to be my "big rides," touring loaded. During the week, I have one day of mashing on my road bike in a hard gear or going for a strenuous mountain bike ride. I have another day of climbing on my touring bike on one of the long gravel climbs in the area and another day of long-slow-distance (LSD) on whatever bike feels good. I do core and kettlebell workouts twice a week, yoga twice a week, and a little stretching throughout the week. My fundamental goal here is to get my body used to riding every day and strong enough to be as comfortable as I can be until I have settled into my touring fitness. I've been pretty amazed by how much time and energy this level of training takes up. Often, I have been too tired to do much else in the day. I can't tell if it's my body adapting to all the exercise or if it's my body reacting to lower doses of caffeine since I recently stopped drinking coffee for the first time since high school.

Variety is Key

Variety and riding with friends is the key to my motivation. For example, I have ridden my touring bike, full-suspension mountain bike, gravel bike, road bike, and even my e-bike on all sorts of rides for training. I also schedule and say yes to ride dates any chance I get. As a result, I build more connections, have fun, and stay accountable to and through this goal.

As I write this, I am starting to switch gears. My body seems to be adapting, and I am beginning to have more energy again. In these last few weeks, I will be focusing more on the mental aspect and getting myself in the best place I can be before I leave. This mental piece looks like wrapping up loose ends for work, i.e., applying for event permits, creating content for Jorja (who is taking over my social media account for this journey), writing blog posts, and communicating with my sponsors. It also means spending quality time with my sweetie, seeing our therapist, working with my life coach, going to my naturopath, and my dentist. Lastly, I still have some studying to do on the route and its resupplies.

It Takes A Village

It has taken a village to get me ready for the Tour Divide, and I do this for a living. The majority of people who will be riding the Tour Divide are average (and privileged) folks who have full-time jobs and even families. I already admire their determination and courage to take on such a committing challenge and cannot wait to meet some of the fellow riders out on course.

How Finding What I Love To Do Outdoors Changed My Life Trajectory

My earliest memory of my love for the outdoors happened on a trip to Kings Canyon when I was 7-years old. My parents packed the van with their six kids and drove the winding road up to the National Park. Along each curve, one kid after the other grew car sick and dropped like a fly. This car-sickness was not uncommon for our bunch, but I was proud to have made it to the top without losing my lunch. At least, until that night when the sudden urge awoke me. I left our family-sized tent, did my business outside, and went back to bed. When I woke the following day, my left eye had swelled shut from a mysterious insect bite. After a quick check-up with the park ranger, my parents handed me a pair of sunglasses and marched all six of us (ranging in age from ten years old to one year old) on an 18-mile hike up the Roaring River. The memories from this trip that stayed with me through my youth and young adulthood were not so much the car sickness and the allergic reaction. They were the smell of the pine forests, the cool crisp air in my lungs, campfire smoke, massive pine cones, and the sound, force, and mist from the whitewater river.

A year after this trip, my family moved to Maineville, Ohio, for my Dad's job. Maineville, at the time, was a small township located in the countryside outside of the suburbs of Cincinnati. We moved to a bigger house on 8-acres of flat and forested land. Surrounding us were fields of corn and soybeans, ash forests, and mossy creeks flowing to the polluted Little Miami River. The first year we lived in Ohio was the first memory I recall struggling with my mental health. I had moved from a cul-de-sac surrounded by my best friends with no limits of outdoor space to explore and play to feeling alone in a hot and humid place that I had very little interest in. Don't get me wrong; I was highly privileged. I was fortunate to grow up in a big family with loving parents. I went from being homeschooled to going to private catholic school starting in the 5th grade, and I got to play team sports such as basketball, volleyball, and eventually field hockey. Despite this privilege and frustratingly so, I still found myself struggling to belong and to have the desire or focus on imagining, let alone pursuing any goals. Life seemed pretty clear at that age. Go to school, get a degree, get a job, find a husband, have some kids, and maybe continue to work. I couldn't say I was too excited about what I perceived as my only option, and as a result, I started to look for thrills in alternative ways.

When I was a freshman in high school, I was suspended from school for leaving a mixer (a co-ed dance) to drink beer between the field hockey field and the nunnery with some new friends. Having learned what we had done, the vice principal prescribed an in-school suspension where I was to sit in silence and do my homework in a 100 square foot office with one of the schools' nuns throughout each school day for one week. The office had clear windows facing the school hallway, so my punishment was on display for the entire school to see. I was also required to see a psychologist as part of the discipline by the school to ensure I did not have any addictions. I was grounded from seeing friends for a month. I recall hearing about the whispers of my behavior from the community at my parent's church. I felt their judgment as I approached to take communion on Sundays. From this moment, I was labeled the trouble-maker in my class, even though this was the most severe altercation I had while at school. If a backpack wound up missing at school, I was called to the vice principal's office to see if I had stolen it (I had not).

This label lived with me throughout high school, and I took it on as my identity. By doing so, I had resolved that that was who I was. Someone who wasn't cut out for school, who partied hard, had promiscuous sex and wasn't afraid to try most drugs I was offered. My idea of what my future could hold had merged from a degree, job, husband, and kids to early pregnancy, jail, or worse. It makes me sad to think about how little I cared for myself during this time in my life, but I am also so grateful that I found a way to turn things around by finding what I loved to do outdoors.

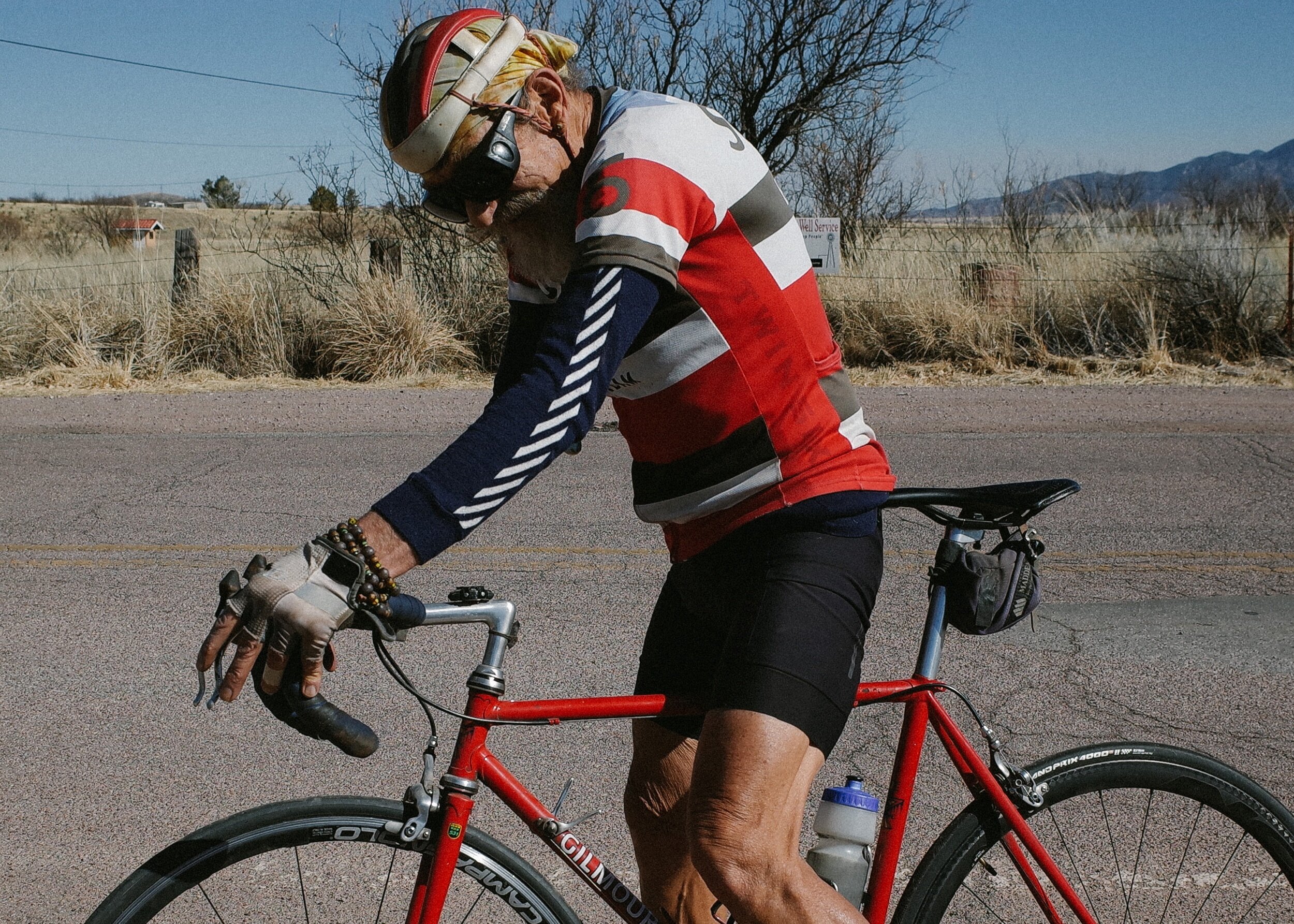

When I graduated from high school, I could no longer lean on field hockey to help me stay in shape. I knew I liked to exercise, but I had always resented the pain, discomfort, and monotony of running. My Dad had been a runner his entire life, having completed over 20 marathons throughout our childhood. His knees, however, eventually stopped serving him, and so he found a new activity. He had chosen cycling just a couple of years before I graduated from high school, and my Mom had picked it up a bit too. So, one day I rode my Mom's Lemond road bike on a road ride with my Dad. I loved how low impact cycling was on my body, how I could see new places, and how it was a great excuse to ride to ice cream with my Dad. For a hardened high schooler, it seems so innocent looking back.

Eventually, I started venturing out on my own to new places, and it was then where I found places that sparked my childhood memories for my love of the outdoors. I found pine forests, rushing rivers, campfire smoke, and pine cones within two hours of my home in Ohio. Once I saw these places, I kept going back. Then, I would go a little further: in Ohio, Indiana, West Virginia, and Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina.

Over these years, my love for cycling coincided with my realization that I love to work with bicycles as well. I worked a part-time job at the Loveland Bike and Skate Rental since I was 12-years old for 8-years. I decided to work at bike shops and eventually managed those shops. I started becoming more focused and driven to graduate from school and did so with honors (for the first time in my life) and a bachelor's degree in history. When I graduated from college, I decided to follow what I knew I loved to do and opened my bike shop, Swallow Bicycle Works. After five years of operating SBW, I signed my first contract with Specialized Bicycles and rode my bicycle across the country on dirt roads following the Trans America Trail (TAT). The rest, at least for this story at this time, is history.

I share this story because I want to illustrate how finding what I love to do outdoors literally changed my trajectory in life and why I am choosing to fundraise $5,000 for The Cairn Project to increase accessible outdoor opportunities for young girls. If I had been able to learn that the outdoors was a place that could provide me the sense of purpose, inspiration, freedom, and adventure I had been seeking as a youth, I probably could have saved myself, my parents, and teachers a whole lot of trouble. I am fundraising for The Cairn Project because I believe they make a difference in the worlds of young girls who are less privileged than I was, where opportunities and chances to be outdoors are few. If you can, please support this goal by donating to The Cairn Project. $5,000 will fund an entire grant to an outdoor organization that helps get more girls outdoors. To donate, click here. Thank you!

Tour Divide Preparation Video: Why, Expectations, and Q & A

I have teamed up with my friend Jorja Creighton of Jambz Distribution to bring you some fresh new content from my Tour Divide journey. In this video I share a little bit about myself and answer some questions about my expectations and preparation for the TDR. A lot of the work Jorja will be doing will be shared via my Instagram account, especially while I am doing the ride, but we’ll have one more video to share about my gear and set-up before I leave. Stay tuned!

The Tour Divide and The Cairn Project

On June 11, 2021, I will line up on the Tour Divide's unofficial start line for, according to the race’s website, is the “longest – arguably most challenging – self-supported mountain bike time trial on the planet”. The race follows Adventure Cycling's Great Divide Mountain Bike Route, which stretches 2,745-miles of dirt roads and single-track from Banff, Alberta, to Antelope Wells, New Mexico, over 200,000 ft of elevation gain through the Rocky Mountains. This endeavor will be by far the most challenging I have ever embarked on, and I do not take it lightly.

📍The Great Divide Mountain Bike Route travels through the unceded ancestral territory of the following Indigenous nations: Blackfoot, Stoney, Tsuut’tina, Ktunaxa, Salish Kootenai (Flathead), Sashone-Bannock, Eastern Shoshone, Cheyenne, Apsáalooke (Crow), Núu-agha-tʉvʉ-pʉ̱ (Ute), Jicarilla Apache, Pueblos, Diné Bikéyah, Shiwinna (Zuni), Chiricahua Apache, and Janos.

As a young person, I grew up with a limited view of what I could do in life. I thought I had two choices: get married, have kids, or get married, have kids, and have an office job. While there is absolutely nothing wrong with going these routes, it wasn't a direction that excited me at a young age. As a result of this mindset, I struggled with motivation during my youth. I was a hard worker, but I was not satisfied, and I was frustrated by it. It wasn't until I found an activity that I loved to do outdoors that I started feeling more confident and passionate. Since then, I have learned to trust myself and forge my destiny by creating a life where I can do what I love to do.

For this challenge, I am teaming up with The Cairn Project to fundraise $5,000 to provide outdoor opportunities for more young women and girls. I have had the incredible privilege and opportunity to make my passion for adventure cycling as my work. I want to help create accessible pathways for more young women and girls to pursue a similar lifestyle, adventure goal, or profession. I never knew this life of mine was possible or even an option. If young women and girls could feel inspired by what I do and see that they could do it too, or to get exposed to what they love to do outdoors at an early age, I think it could make a positive impact on their lives, and the lives of others around them.

Over the next few months, I'll be fundraising for The Cairn Project by sharing my story as a young girl and how I found purpose in life through riding my bicycle as I prep my mind, body, and equipment for one of the most significant endeavors of my life.

In the meantime, you may be curious to know how someone who has sworn off bikepacking races for the past six years has landed on this ambitious goal. Numerous factors have influenced my decision.

Like so many others, riding the entirety of the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route has always been on my bucket list since I watched the Ride The Divide film in a movie theater in Cincinnati, Ohio in 2010. At the time, I recall thinking that I could never do something like that. Then, five years later, I rode my bicycle 5,000 miles in three months from East to West across the U.S. following the dirt roads of the Trans America Trail (TAT), a dual-sport motorcycle route. The TAT was my fourth bike-tour.

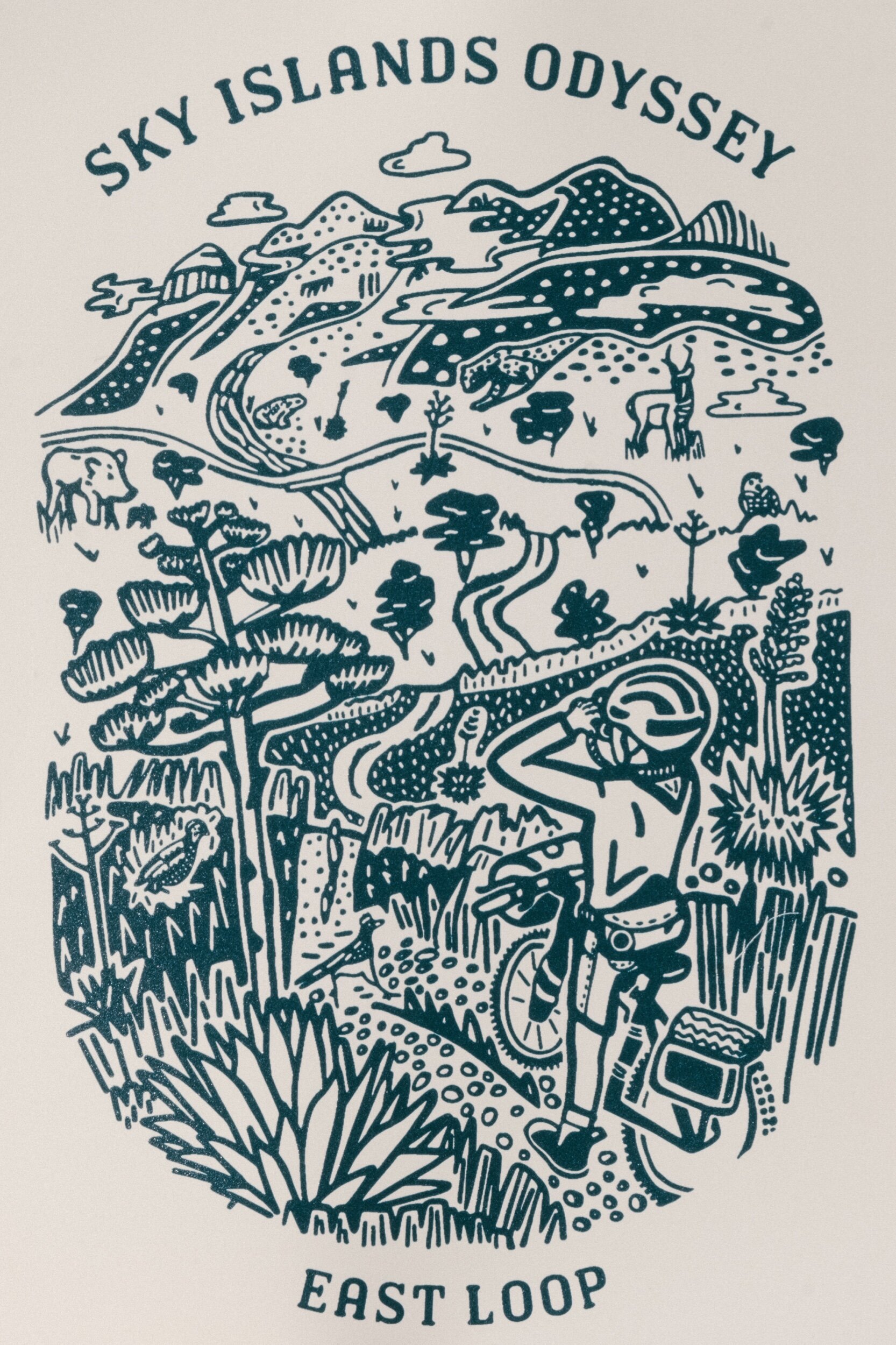

"So why race it? Why not just tour it?" asked Jon, a fellow bikepacker camping at the Appleton-Whittell Research Ranch during his ride on the Sky Islands East Loop. I always imagined doing a slow tour on the GDMBR with my parents or a sibling who wanted to make a cross-country trip; because of all of the support and infrastructure, it seems like the most accessible off-pavement route to tour on. Until one or all of them are ready for such an endeavor, my interest in touring and moving slowly through a landscape for over a month lies in places that are new-to-me in every sense; terrain, culture, and food. I love that type of stimulation and challenge from bike tours.

I am approaching the Tour Divide as a solo challenge for myself. Adam, my number one adventure partner, will be tied up in grad school for the next year, which means I’ll be doing a lot more of the bike tours that fuel my soul on my own for a little while. My friend, Arya, planted the seed by committing to do the Tour Divide this year. I haven't seen her in over a year. While we both intend to travel at our own paces, just knowing she is out there gives me a tremendous sense of comfort and motivation.

After six years of touring and experience, I want to see if I still have a challenge like this in me. I think I do. The challenge is to finish in under 32 days which is all the time I have to spare before I fly to Iceland for the Rift Gravel Race. My goal is to have fun and to stay healthy while doing it. 2,745 miles in 32 days still requires averaging 86 miles per day of riding. Part of me hopes to do this a bit faster than that, but I'm keeping expectations low because I have no idea how my mind and body will react when faced with such a highly rigid daily expectation. I could see myself losing motivation, needing to slow down to enjoy my surroundings a bit, and possibly not finish the whole route. Or, I could settle into a good rhythm, find that sweet blissful spot of pedaling all-day every-day and end up riding more miles than I think I can do right now. Of course, I hope for the latter situation and am doing everything I can to prepare myself to be in the best possible shape before I start.

I'm not going to lie. Telling people I am doing this has been terrifying, but it is also holding me accountable to this goal. It's nothing new for me to feel questioned, doubted, overly ambitious, or "crazy" for believing I can do something like the Tour Divide. I realize that these feelings are more my internal saboteur and that learning how to work through those voices is one of the first challenges of this entire endeavor.

I am excited to share my experience preparing for the Tour Divide over the next couple of months. Please help me kick off this daunting journey to the start line by donating any amount to my GoFundMe campaign through The Cairn Project. Thank you so much!

COVID plan: I will be getting my jab in Durango on Friday, 4/9. I hope that due to the improved COVID situation in the United States, the border with Canada will open before the event starts (it is currently closed through April 21, 2021). If the border does not open, and the Tour Divide's grand departure does not happen, I intend to do the ride, at the same time, with the same goals, starting from Eureka, Montana.

Goodbye Arizona

The temperatures are getting warmer down here in southern Arizona. The leaves on the cottonwood trees were yellow when I arrived in November, dropped their leaves in December, and have now grown back green and lush. There are shoots of green grass sprouting up everywhere. New-to-us bird species pass through the yard, such as hummingbirds, Little egrets, and Vermilion flycatchers. The Morning dove's songs are constant, an indicator of warmth. Western rattlesnakes are emerging from their holes to bathe in the sun. The pollen is off the charts, flowers are blooming on the cacti, and I am allergic to everything. It's time for me to say goodbye to this place until next winter and return to Durango, Colorado.

As I write this post, we are packing up our belongings and saying our goodbyes. Goodbye to the view of the Mustang Mountains from the dining room table. Goodbye to our feathered, furred, and scaled neighbors who provided constant entertainment and curiosity. Goodbye to the long exploratory day rides with friends and the afternoon bike rides around the ranch bathed in golden light. Goodbye to the Sonoita characters, to Cristina, Ben, Suzanne, and all the bicycling visitors who shared a conversation and a beer over sunset at the ranch.

With Covid cases on a significant decline in the region, visitors could return to the ranch over the last couple of months. My parents came and so did some close friends. Many of the visitors were bikepackers passing through along the Sky Islands Odyssey routes. Due to having so many separate lodging buildings, camping options, and outdoor conversing spaces, the ranch provided an opportunity to meet new people and to spend time with loved ones in a safe way outdoors. I appreciate these interactions more than I ever did before Covid.

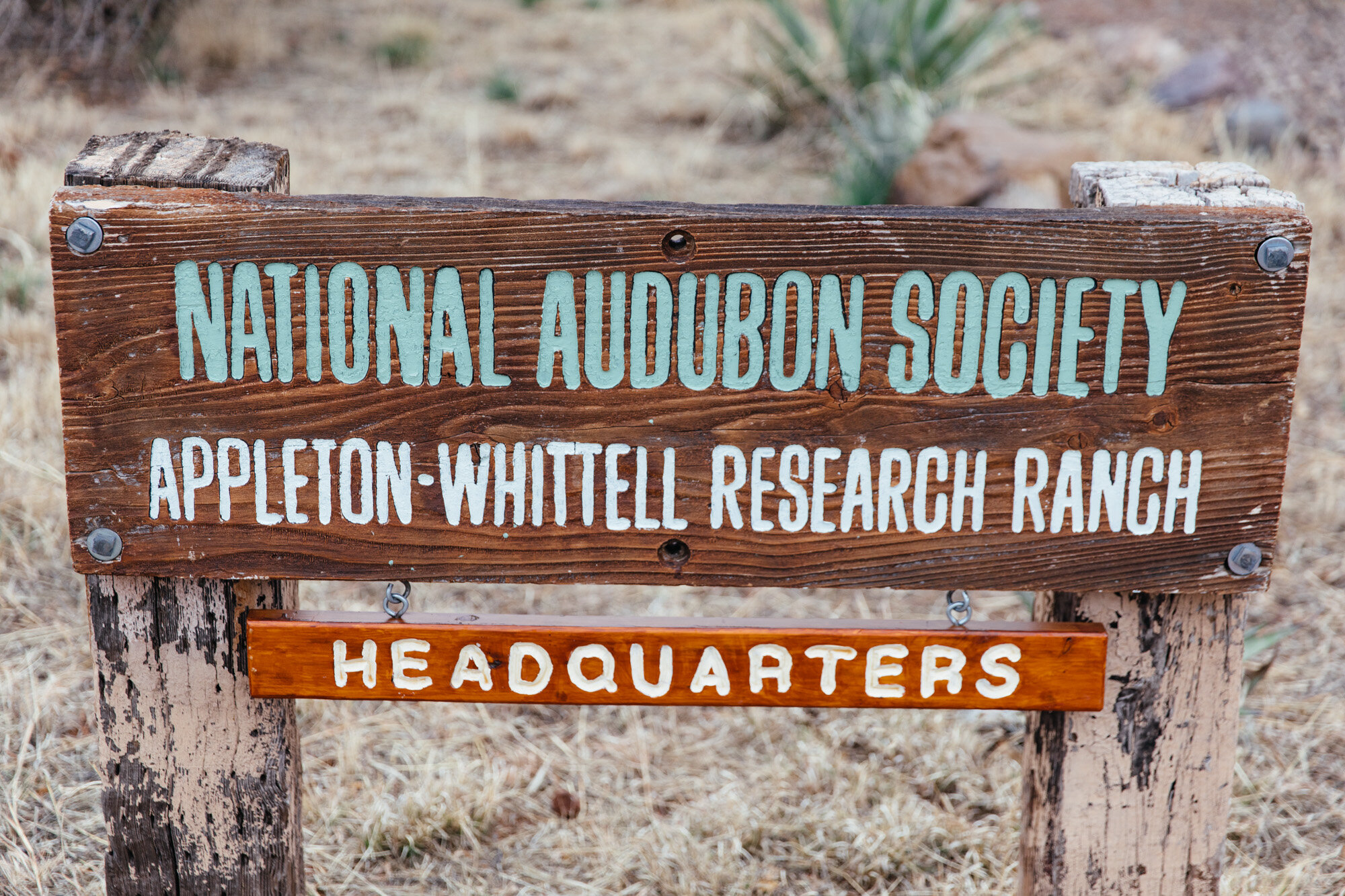

At the Appleton-Whittell Research Ranch, we have laid a solid foundation for the future of more cycling infrastructure and opportunities at the ranch, so stay tuned. Incorporating bicycles into the daily operations and outreach of a non-profit wildlife sanctuary that used to be closed to the public before 2018 is a slow process but certainly one of the most exciting ones to me. I'm looking forward to returning in November to pick this work back up and to share this place with more of you.

Over the last few weeks as we have been cramming in last-minute experiences for ourselves by venturing off the ranch to do some new-to-us rides in different parts of Arizona. One of the days, Hubert, Sean, Adam, and I tackled a single-day ride on the Arizona Trail from Picket-Post Mountain to Kelvin, a 36-mile ride on 100% single track with over 3,500 of climbing (and we were riding it in the downhill direction!). This ride follows an incredible and remote section of the Arizona Trail and one of the few consistently rideable single-track sections of the entire trail system. It was so cool to see the number of people from all over the world, thru-hiking and bikepacking this section. The Arizona Trail is truly a gift to Arizona and the world! Our ride's biggest challenge was that we just so happened to time our ride with the first major heatwave of Spring with temperatures reaching into the low 90's. Even with nearly 4 liters of water per person, the tole of a big day on challenging terrain and sun exposure resulted in chaos by the end of the ride. We all ran out of water with 5 miles to go, Adam abandoned the final climb of the route by bailing to the railroad tracks, and Hubert and Sean ended the ride with a medium case of heat exhaustion. We were lucky that their conditions improved eventually, and we did not have to call in support. This was a humble reminder that the heat in Arizona is no joke, to only stop in the shade for breaks, drink plenty of water with electrolytes, and cover up as much as possible. After some time to recover, we cooled ourselves down by floating the swollen Verde River the following day.

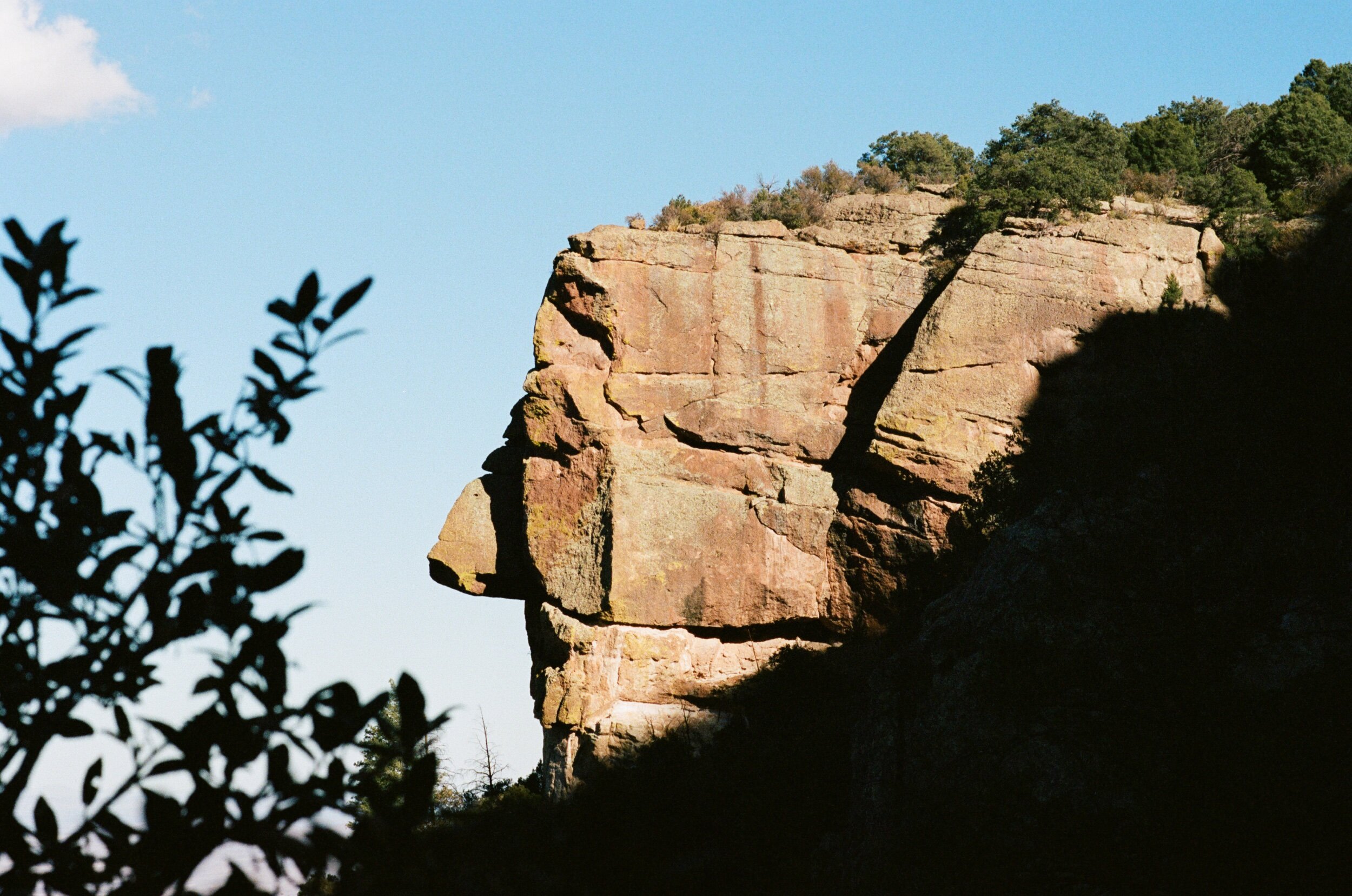

We also visited Sedona for some more mountain biking, which was my first time being there. Wow, is that place stunning and swarming with people. The single-track was incredibly fun and the perfect amount of pucker for my developing mountain bike skills. The crowds of people made me feel like I was in some weird natural amusement park. The landscape of red sandstone bluffs, cliffs, and slick rock immersed in evergreen cedar and pine forests, dotted with prickly pear and agave, was something out of a Jurassic Park or Star Wars movie set with tourism helicopters flying overhead. I didn't have the time to help plan these trips. Instead, our crew relied on the incredibly informative and hilarious graphic guides by the one and only Cosmic Ray and his Arizona guide book, Fat Tire Tales and Trails: Arizona Mountain Bike Trail Guide (New Mighty Moto Locals Only 23rd Edition). Cosmic Ray just recently passed away, and while I never had the chance to meet him, our crew honored him by staying true to his recommendations for route choice and flow direction. We were sure to quote all the salad bars we found ourselves in, too (according to the "G-narly G-lossary of Arcane Trail Jargon" in Ray's Book, salad bar means turfing it into the shrubbery. "The shmorgy of shred").

While the last few weeks have been hectic, I'm savoring these final moments and looking forward to slowing down a bit in Durango. I didn't get to see everyone and do everything I wanted to during my stay in Arizona. Still, I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity to spend time here, especially during such a challenging year. I am confident that the winter of 2021 and 2022 will bring more opportunities to be together, to share a ride, a sunset, and a conversation.

I'll be changing my focus back in Durango. I will be assistant coaching for Devo Exploras, a 6-8th grade all-girls bikepacking group, and fundraising through The Cairn Project to create more opportunities for young women and girls to get outdoors. All the while I will be preparing my mind, body, and equipment for the Tour Divide Mountain Bike Race in June.

While I will miss the beauty and the solitude of southern Arizona, I am looking forward to being back in Durango, having fewer splinters daily, taking baths, being around trees, floating down the Animas River and not driving an hour and a half to the grocery store for a while. Thanks as always for reading my ramblings. On to the next chapter!

E-Bikes: My Initial Impressions

I got an e-bike. It's true. Why not? Some of you may be concerned, saying to yourself, "What is the world coming to? What has the impact of isolation done to Sarah Swallow?"

The Controversy

E-bikes, also known as pedal-assist bikes, are certainly controversial within purist cycling circles. From what I understand from the conversations I have had with people on different sides of the debate, is this: some people feel like e-bikes are equivalent to motorbikes, and if you allow e-bikes access to non-motorized trails, it could lead to more motorbike access on those trails. Others feel like e-bikes on mountain bike trails create dangerous situations because e-bikes can travel at a higher rate of speed and can more easily cause collisions between cyclists. Another segment feel that e-bikes degrade the wild experience of traveling through the backcountry, exclusive to people who can get there under one hundred percent human power. Others fear e-bikes could create the racer-joe-on-a-bike-trail experience that we've all had, where we will be enjoying a slow pedal, a deep conversation, and the surrounding beauty to the cry of "on your left!" and a swooshing sensation that you can hear and feel. The shock sends your hands momentarily off the handlebars and your bike into the ditch. That's what some people think e-bikes will do to their peaceful experience in the backcountry.

Much of this debate is explicitly related to e-mountain bike access in the backcountry, where I am about to share my experience riding an e-gravel bike. Regardless, my experience riding my e-bike has led me to an initial opinion about the arguments I outlined above. I find e-bikes closer to real bikes than motorbikes by a long shot, but I cannot yet speak to what we should do for access on non-motorized trails. I don't want to open the door to more gas-powered motorbikes damaging trails, but I am confident that there are solutions to opening trails to e-bikes and not motorbikes. I think e-bikes have the same level of impact as regular bikes on trails. I also believe that the chances of getting spooked from a one hundred percent human-powered racer-joe-on-a-bike-trail and a sixty percent human-powered, pedal-assisted racer-joe-on-a-bike-trail are equal. I don't think it is fair to use most of these concerns as evidence for excluding entire populations of people access to the backcountry. I find these arguments problematic for our mission to promote inclusivity, accessibility, and relatability to beautiful natural landscapes, which in turn, has immense potential to create more advocates to conserve these spaces.

While I am here, I'd also like to acknowledge that e-bikes currently are still quite expensive, limiting accessibility to anyone who can afford $2,800 to $15,000 from Specialized Bicycles. Still, there are many other options and price points out there. I expect that in the years to come, these bikes will only become more affordable.

I imagine I will be leaning into the nuances of accessibility a bit more in the coming years as I spend more time at the Appleton-Whittell Research Ranch, a place that feels very much like a wilderness area to me. The AWRR reduces human impact as much as possible so that researchers can study the effects on the habitat. Still, at the same time, the ranch also needs to increase engagement, accessibility, and appreciation amongst the public to sustain and share their work.

I have found myself in the camp of always being e-bike-curious. I suppose the fear of the stigma of getting hooked on electric-assisted bicycles, which would lead to an abandonment of the mechanical genius that is a strictly human-powered bicycle, and falling into retirement, or the idea of giving up has held me back from committing to ride one. I imagine that some of my analog cycling friends rolling their eyes in disgust at my desire to ride and even write about e-bikes. I value and appreciate the aesthetics of their classic custom bike builds, colorful and artistic components and frame designs. I have even owned my fair share of beautiful custom bicycles. But since I have moved away from bike shops and no longer have access to the tools, space, wholesale pricing, and expertise that I used to have, my priorities have shifted. These days, I don't feel like I have the money, time, or creative energy to create custom bike builds. That's not where my energy lies at this point in my life. I'd rather be designing a route, riding that route, writing, reading, or just scheming for future projects. I blame it on the fact I am a millennial. I didn't grow up with knowledge of or experience with "classic" bicycles. I like fashion and cool bike style and do what I can with what I have because it makes my bike feel like an extension of my personality. Don't get me wrong, the fact that I have been sponsored by Specialized Bicycles for the past six years and have signed on with them for the seventh year no doubt influences my perspective here. They have been generously fueling my passion for riding with bikes that are reliable, comfortable, and light enough to inspire me to want to climb over 17,000 ft passes in the Andes loaded with around thirty pounds of gear, food, and water.

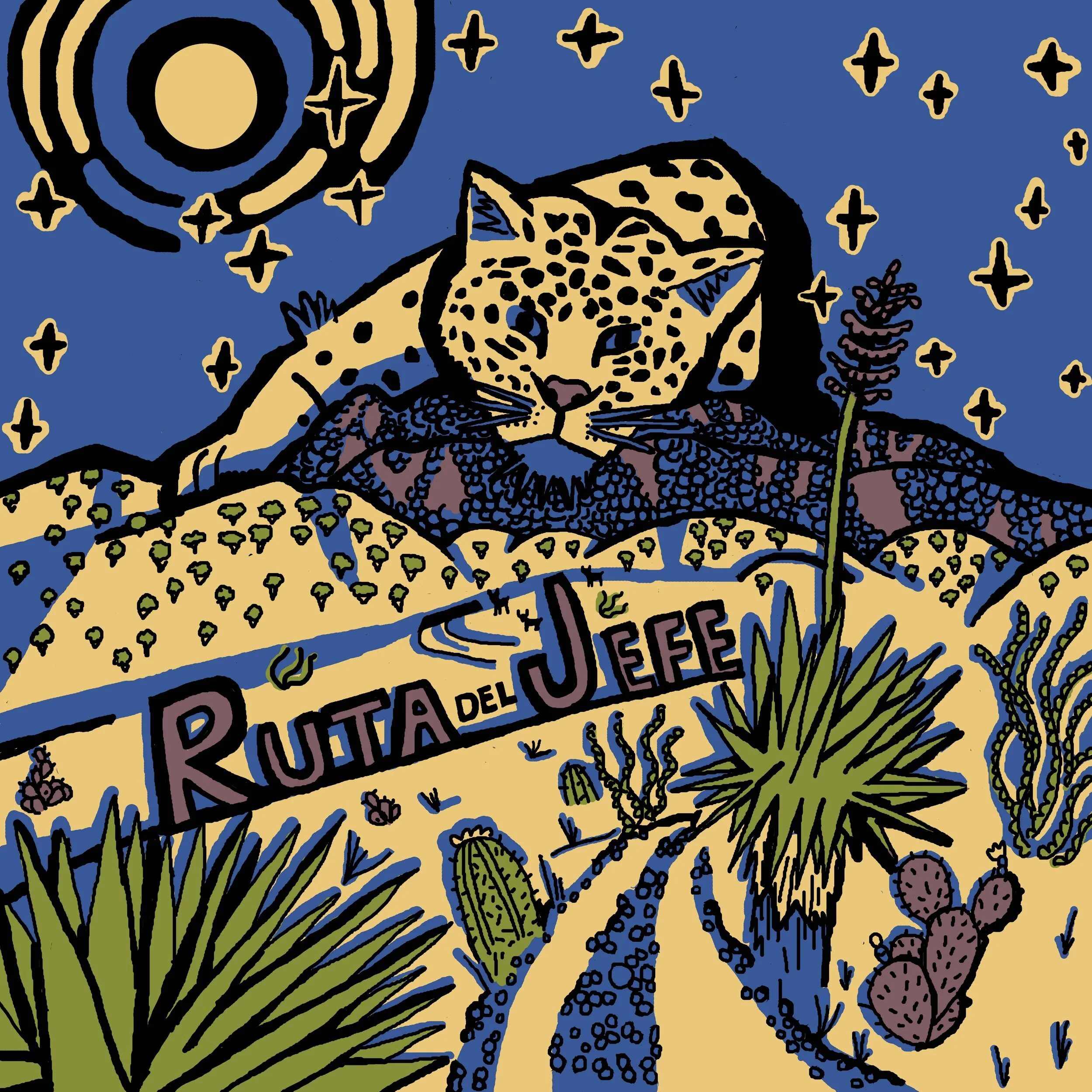

How I Became E-Bike Curious

My e-bike curiosity significantly increased in 2020 and started after I got my first taste of e-bike life at Ruta del Jefe (RDJ) at the AWRR last February. There are two different lodging and research compounds at the ranch; the lower east side compound includes the Swinging H ranch house (where I am currently living), the bunkhouse, the casita, and the lab. This lower zone is where bikepackers who are riding the Sky Islands Odyssey route camp. A mile up the road to the west are the headquarters, the director’s and conservation program manager’s residences, the barn, and additional camping space. I host the festivities for Ruta del Jefe up here by the headquarters. For last year's RDJ, my Mom brought her new e-bike, a Specialized Turbo Vado, to go on gravel rides with my Dad, who is always training for some ultra-endurance gravel event. She can keep up and even ride ahead while he can do his training ride, and they both get to spend an excellent time together on bicycles.

In the mornings at RDJ, my Mom would ride her Vado from the Swinging H up to the headquarters to help volunteer. Once her Vado was there, I would wisp it away to get around the ranch quickly to-and-from various places a mile or two apart to do the random tasks required to put on such an event. These were some of my favorite moments from the event because they were a burst of fun personal time, a much-needed break from the intense focus I had managing operations, and they helped sustain my energy throughout the weekend’s festivities.

Then, there was the inaugural RDJ scorcher race. A scorcher race is a mix between a cyclocross race and a fixed gear criterium completed on a fixed gear gravel bike. As far as I know, Ron, aka Ultraromance, aka my friend Benedict Wheeler created this super ultra-niche with enabling from friends and frame builders, Adam Sklar and Hubert d'Autremont. Not very many people own fixed gear gravel bikes, so scorcher races are open to all bikes and riders who would like to race a four-mile undulating gravel loop two times in a row at full gas.

As I recall, ten ambitious souls lined up at the start line for the RDJ 2020 inaugural scorcher race but the finale between Benedict, Adam (both on official scorcher bikes), and Jorja (on my Mom's Vado e-bike) was most memorable. With less than a mile to go, the three were riding neck and neck, seeing triple, and tasting blood; then, Adam dropped off the back leaving the glory to be decided between Benedict and Jorja. It was wheel to wheel as the final two rounded the corner to the finish line. Before anyone could believe what they were seeing, Benedict (in his true character) grabbed Jorja's handlebars. Simultaniously, he pushed her back as he propelled himself forward over his bars and slid head-first through the gravel and across the finish line. I was dumbfounded at the fact that the person tasked with feeding seventy-plus people in thirty minutes was covered in blood, gravel, and sweat for the sake of his vanity. But alas, it was a truly memorable finish, shenanigans of which will live on through campfire stories for years to come.

As I watched Jorja ride the e-bike during that scorcher race, I couldn't help but think how fun that looked. In the year since, I welcomed every conversation about e-bikes I could with people; some of them were inspiring, fun conversations with a lot of giggling, and some were heated debates. Throughout it all, the tales of the benefits of equalizing the pace of cycling for partners, the ease of running car-less errands, and generally how much fun e-bikes sounded appealed to me. When I moved to the AWRR for the winter and started to grasp how remote and isolated it was from the nearest town with services, I seriously started thinking of getting an e-bike for myself. I only had to mention that I was e-bike curious for Specialized to have a Turbo Creo SL Expert EVO (an e-gravel bike/e-diverge with 250 watts) at my door the next week.

Three E-Bike Rides

Since I received the Creo SL, I have taken it on a handful of rides. In particular, three rides stand out for my initial impressions of e-bikes and the potential I see for my specific uses. I must say, when a bike inspires me to think of riding creatively on new types of rides for different purposes, I feel like that's the sign of a good bike. The Creo SL is creating a refreshing level of fun and joy in my life, sensations that have felt a little muted this year due to the pandemic, social isolation, and the state of societal and political affairs.

The first ride I took the Creo SL on was a thirty mile round trip ride that was thirty percent dirt and seventy percent paved to get cash from the closest ATM in Sonoita to pay the guy who was delivering firewood in two hours. I finished a meeting, quickly pulled on some skivvies, filled up a water bottle, and dashed out the door. I put the e-bike on full throttle (3 out of 3) mode and pedaled as fast and as hard as I could. The speed was thrilling and addicting, and I settled into a pedaling pace shifting between the hardest three gears for the rest of the ride. Head down, hands in drops; I was riding at an anaerobic threshold compared to the speed I ride in the first thirty miles of a gravel race. The thing about e-bikes, at least in terms of my e-bike, is that they are pedal assisted, so it only will go as fast as you push it to go through pedaling and momentum. Stopping either of those two things causes the bike to throttle down, and its full weight to be felt as if you are climbing a hill in too hard of a gear. That's why once I got it revved up, it felt like it was best to keep it that way, and it became a fun game and good work out. I finished the ride (including stops at the ATM, opening and closing the ranch gate twice, and taking a picture) in one hour and twenty-six minutes. That's about a twenty mph average, including stops, which I think is a testament to the fact it is merely an assist, not a motorcycle. I came away from this ride feeling like I had gotten a perfect anaerobic workout while also accomplishing an errand relatively quickly without having to drive a car. My core was tired as it always is, but my legs were not throbbing as they would have been if I had made the same effort on my Diverge. I also had more battery remaining than I expected and wished I had just left it on full mode, rather than lowering it to 2 out of 3 mode halfway through the ride, but I was too scared to have to ride a dead, heavy e-bike on some of the hills leading to the ranch.

The second ride was a quick school break ride with my partner, Adam, or the "Lorde," as some know him. Adam has been using his time during COVID to earn his master's degree in social work to pursue a lifelong journey of mental wellness for himself and others by becoming a clinical therapist. Getting a master's degree and doing personal work, learning, and unlearning the habits required to meet one’s basic needs and enhance social functioning, self-determination, collective responsibility, and society's overall well-being is no easy task. To help, we have restructured our lifestyle to accommodate a fixed schedule for the first time in our relationship. This new schedule of classes on Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday has significantly diminished the distance we can travel, time spent bike touring, and on rides together in general. This adjustment just so happens to complement the need to limit our travel and activities due to COVID anyway.

These days, Adam doesn't always have the time to go out on my all-day-long exploration rides. He needs short and efficient study break rides so he can get his nose back in the books as soon as possible. Usually, I shy away from these short study break rides because Adam is quite strong and fast, and for me to tag along would mean I'd sign myself up for a torture fest, one in which I'd quickly lose the desire to try and keep up for. However, the last time he wanted to get out for a quick ride, I tagged along with the e-bike. Each of our competitive sides quickly came out to play, first by talking a little smack, then came the mental manipulation games and a false start on a climb, and then came the race. It didn't take me long to prove to Adam (someone I have had fierce debates over e-bikes) that I could out-pedal him. He could keep up in some places for a short time, but overall, that was it. With this confidence, I settled into a parallel ride where Adam pedaled consistently hard, I could stop to take pictures, pedal hard to catch up, pull him or ride with him for a bit, and finally pedal off the front and stop again to check something else out. This ride was enjoyable, served both of our needs, and equalized the ride's overall pace. I wasn't frustrated with him going too fast, I wasn't exacerbated by how hard I had to keep up, and I didn't have any guilt for stopping. I could jump into anything I wanted to do on the ride while also sharing a ride with him. On the other hand, Adam gets my company on a short and fast workout and is pushed to limits that equal the Durango Tuesday Night Worlds group ride.

The third ride I took my e-bike on was one part scouting mission, one part errand, and all parts adventure. I decided to go for a ride that had been on my list to scout for a while. I wanted to ride the old railroad grade through the adjacent Babacomari Ranch, which I have gained permitted access to by living here. I planned to follow the dirt railroad to Huachuca City and then take pavement to and through Fort Huachuca to renew my residents' pass to gain access through the base which is slightly a shorter drive to the full services of Sierra Vista from AWRR. Ultimately this errand would save me close to two hours of driving.

The first part of the ride, the scouting part, was an enjoyable spin where I took in the beauty of my surroundings, enjoying the fresh cool damp air, and the grippy dirt from the rain we had received the day before. I had the pedal-assist set to 2 out of 3, which felt like it perfectly matched the amount of effort I wanted to put in. Once I got to the pavement and the busy four-lane road leading to Fort Huachuca, I put the bike in 3 out of 3 mode and turned on the hammer. I rarely will subject myself to roads like these because I feel like they significantly increase my chances of being hit by a car. I was reminded of this when a red truck with four muffler pipes sticking out in different directions pulled into the shoulder I was riding in, laid on the horn, and passed closely at high speed. This experience only made me pedal harder, and I was grateful for the assistance that shortened my time on that road. When I finally reached the Fort, storm clouds loomed overhead. It looked like I would get stuck in some rain without a rain jacket. Having not seen rain in over two months (aside from the previous day), I had only brought my wind jacket. As soon as I got my permit for the Fort, I hopped back on my bike to try to beat the rain. I had 15 miles of rolling hills to go, and I had only a quarter of power left. I rode on 2 out of 3 mode until the final power light quickly went red, at which point, for the first time, I rode in one 1 out 3 mode. I could feel the bike's weight more; the hills and the effort to climb them felt as hard as a regular bike. However, there was still the looming fear that I would have to pedal a dead heavy e-bike on the steep rocky miles leading to the ranch, which motivated me to pedal harder to not to waste any remaining battery life. Finally, having gotten only a little wet and cold, I reached the ranch road, still with one red bar of power left, and pedaled my way home. I was exhausted from the unexpected challenge that the e-bike had created for me through inspiring a false sense of confidence, distance, and capability. This time, my legs hurt, my body was sore, and I even required a mid-day nap the following day.

My Impressions

In essence, I am a fan of e-bikes, pedal-assist bikes; whatever you want to call them. I certainly would love a longer battery life and wider tires, but I'm sure that's all coming in the near future. I don't see myself ever riding an e-bike on group rides with friends who are not riding e-bikes, but I am interested in going for e-bike group rides. For the most part, I see it as a tool for more solo scouting rides, commutes for errands, or quick-school-break-rides with Adam. Living in a place that has four miles of gravel each way to get on and off the ranch, I am more inclined to ride more frequently off the ranch to explore the surrounding areas on my own with the Creo SL. It promotes quick, low-impact mental health breaks, solo physical workouts, and tilts the scale in my favor on short, fast rides with my partner. The result is that I am riding more, driving less, seeing more places in a shorter time, getting stronger (through riding more frequently), and having a ton of fun.

Living On The Research Ranch

It's been over two months since Adam and I moved down to live at the 8,000 acre Appleton-Whittell Research Ranch (AWRR) 100 miles south of Tucson in Elgin, Arizona for the winter. For an introduction to the research ranch and what I am doing here, feel free to read my previous story about living at the AWRR.

On a bike tour the extent to which I typically go without seeing another person rarely exceeds three days. Scatter back-to-back three-day periods across three months, and you can get a good idea of how isolating it felt to ride the Trans America Dirt Road Trail, also known as the TAT. The 5,000-mile tour of the TAT back in 2015 was the most isolating experience I have had, until recently. Living on the AWRR during a pandemic has been an unexpected level of isolation I have ever known. This adjustment dominated what feels like the whole month of December. During this time Adam and I worked on getting the Swinging H ranch house, which is over one hundred years old, cleaned and fixed up into a more livable space for our five month stay. Because no one has lived in the Swinging H consistently for over twenty years, this project included getting it set up with hot water, internet, safe electricity, wood for heating, fewer cobwebs, less dust, and deterring mice and woodpeckers. We did all of this with the constant help and support of the ranch director and staff, Cristina, Ben, and Suzanne.

Contributing to the isolation of the research ranch's geographic location being 45 minutes from the closest grocery store and closed to visitors due to high Covid transmission rates in Santa Cruz County, is that there is minimal internet access. The only type of internet available at the research ranch is satellite internet, which requires sending radio signals to a satellite in space, which then beams the internet to the dish attached to the house. Most people have fiber or cable internet, which is typically instant and unlimited. Satellite internet is the new thing for folks who live in remote locations where cable and fiber is too expensive or impossible to install. For reasons beyond my understanding, satellite internet is limited to 100 Gb per month and delayed. Apparently, Elon Musk is working to improve the landscape for the future of satellite internet, but I am skeptical. Since moving here, Adam and I have taken a scrupulous approach to our data usage. We have cut out anything unnecessary to preserve what we have for video calls with friends and family, meetings, ten hours of zoom school per week, homework, and photo uploads.

Do you know what uses up a lot of unnecessary internet data? Instagram, Tiktok, and Netflix. I have largely stopped using these platforms during my stay here. I say largely because I will typically sneak a peek at the Tiktok videos my sisters send me. I'll also occasionally check my messages on Instagram via my web browser on my phone. Instagram is terrible to use through the web browser, but I use it because having the app is too easy and can quickly become an unconscious habit. As a recovering addict, I do not want to make it any easier to score my fix.

Overall, this detox feels like what I have needed for a long time. Whenever I feel lonely, I remind myself that Covid is mainly responsible for this, considering that the ranch would be open to regular bikepacking visitors riding the Sky Island Odyssey routes. I would also typically be preparing for Ruta del Jefe at the end of February, inevitably hosting a few gravel camps, as well as socializing with locals, fellow snowbirds, and whoever was in town visiting for the week. While I am certainly missing my friends this winter, in this social and streaming void, I have been embracing the space, time, curiosity, and interests that living on a research ranch inspires. Over the last couple of months I have had more time to ride, read, write, and cook; so much cooking, in fact, that I earned the nickname "Chef Fireball."

I have been riding my bike on and off the ranch, test riding zones I overlooked in the past. I am finding so much more than I anticipated and using this new information to update my current route offerings in the area and to develop some new ones. Despite its large and diverse road network, routing in this part of the world has never been easy due to nearly every base map being incorrect or outdated. I suppose the challenge is what makes it so fun and why I enjoy exploring down here so much.

I also have been reading about all the facets of the research ranch to inform my writing for some relatable and digestible educational signs and brochures for the average visitor. Thanks to contributions from former ranch directors Carl and Jane Bock and the University of Arizona Press, there is an abundance of literature written about the AWRR and the surrounding area. This library has provided me with an education of the history of the research ranch and livestock grazing in the Southwest; semi-arid grassland habitats; archeology of southeastern Arizona; and the endangered Chiricahua Leopard Frog. I am learning how humans have used land throughout history to our benefit and coming to terms with the impact that use has had on the land. Living on the research ranch, a semi-arid grassland not grazed by livestock in over fifty years, I can make these connections in a more personal way and see the positive effects of limiting human use first-hand. It seems that we humans are the invasive species spreading, choking out, and taking over native habitats for our greedy benefit.

Grasslands vs. Livestock Grazing

My time here has turned me into a grasslands snob, which is a blessing and a curse. When I ride off the ranch, I can't help but turn my nose up at some of the surrounding grasslands for how short and overgrazed they look or how many of them have been reduced to dirt and replaced with hoof prints and cow patties. This experience, coupled with my new knowledge, has led to an aha moment in understanding how detrimental the livestock grazing industry has been to the environment by eradicating biodiversity and beauty from natural landscapes and viable habitats for endangered species, specifically throughout the Southwest and Intermountain West. This information compounded with the knowledge that methane from the livestock industry contributes to 14.5 percent of the global greenhouse gas emissions has led me to cut meat out of my diet again. This time, however, not eating meat has been easier than it ever has been in the past.

The Christmas Bird Count

A highlight of the last couple of months was participating in the annual Christmas Bird Count, or CBC, where I spent an entire day moving slowly through the habitat within one or two miles of the Swinging H ranch house and recorded each bird species seen and their amount. Administered by the National Audubon Society, the CBC is a census of birds in the Western Hemisphere performed by volunteers. The count results provide population data for use in research and conservation biology but it also just so happens to be a fun recreational activity. I credit Aaron Van Geem, a friend and wildlife technician who joined us for the count, for making my first CBC an impactful and memorable experience. Aaron is trained and certified to track most animals in the western U.S. for conservation agencies and has worked specifically with jaguars, pygmy rabbits, bobcats, and Mexican spotted owls. What a job! While I have a good sense for spotting critters and Adam can identify different types of birds, Aaron was able to identify each specific species, including their gender and age. As a team of three, we allowed ourselves to fully geek out on birds from sunrise to sunset, at the end of which we were all thoroughly exhausted. This experience provided me with a greater appreciation of the biodiversity in this place where I get to live and cemented the species who also call it home into my memory.

Swinging H Ranch House

A few facts about the Swinging H ranch house; it was part of a separate ranch acquired by the Appleton family when they formed the Elgin Hereford Cattle Ranch over 20 years before selling their cattle to dedicate their land to be a research station in 1967. As we call it, the “H” is part of a lower compound of buildings on the research ranch about a mile from the headquarters, directors and conservation managers' residences and the barn. The area around the H includes a bunkhouse, casita, and a lab. It's nestled lower than most places on the ranch in O'Donnell Canyon at 4,700 ft, surrounded by rolling hills of grasslands and the occasional oak or sycamore tree. We heat this old house by schlepping thirty-to-forty-pounds of oak and mesquite into the house twice per day, splinters and all. The living room window inside the H offers a distractingly good view of the Mustang Mountains. The backyard, creatively landscaped with ocotillo, sotol, agave, prickly pair and blooming yucca, serves as a playscape for many neighborly birds: the Rufous and White-crowned sparrow, Canyon towhee, Lesser goldfinch, Curved-billed thrasher, Pyrrhuloxia, Loggerhead shrike, Roadrunner, and even an occasional visit from the local American Kestrel.

Wind

The weather of a semi-arid high grassland plain in the winter is a lot like living in Ohio in the sense that you can experience a 70-degree sunny day, 3" inches of snow and a tornado all in one week. A tornado is an exaggeration for southern Arizona, but the sentiment is the same when there are days where the near-constant winds increase 30-40 mph speeds. These days, the wind creates an eerie, unsettling howl through each gab of this old house. I typically hunker down inside, taking refuge from the intense conditions outside, and watch as the grasses blow as if they were waves in a stormy sea. Sometimes, I will venture out into the wind to get a break from the house and I am usually pleasantly surprised by how fine it is to ride through, primarily because of the massive tailwind for half the ride.

Time

Time feels like it is simultaneously flying by and not moving here. Part of me is overwhelmed by February already being here, and part of me feels like I have lived here for over a year. It is not uncommon for me to wear the same pair of wool-leggings for five-days straight. I am cherishing these moments with the expectation of a busy February with the ranch gradually opening back up to bikepackers; a tour on the Sky Islands Odyssey full loop for a film project with REI and Ford Motor Company; visits from a small cohort of friends from Austin, Texas; and my parents driving in from Ohio. Note: Adam and I are scheduled to quarantine and be tested before and after each of these visits to combat the spread of Covid.

My time at the research ranch will be coming to an end in April. In the meantime, I still have much I would like to see, learn, and do during the rest of this winter and making a list for winters to come.

Here is a list of some of the great books I have been reading during this time:

Amann, Andrew W. Jr. Bezy, John V. Ratkevich, Ron W. Witkind, Max. Ice Age Mammals of the San Pedro River Valley. Arizona Geological Survey, Tucson

Bahre, Conrad J. 1977. Land-Use History of the Research Ranch, Elgin, Arizona. Journal of the Arizona Academy of Science.

Basso, Keith H. Wisdom Sits In Places: Landscape and Language Among The Western Apache.

Bock, Carl E. Bock, Jane H. The View From Bald Hill: Thirty Years in an Arizona Grassland

Bock, Carl E. Bock, Jane H. Sonoita Plain: View from a Southwestern Grassland.

Sayre, Nathan F. Ranching, Endangered Species, and Urbanization in the Southwest. 2005. The University of Arizona Press

A Getaway in the Chiricahua Mountains

Photos by Hubert d'Autremont. If you like handmade custom bicycle culture consider supporting Huberts work by purchasing a Rangefinder Book.

The Chiricahua sierra has been on my list of places to visit in Arizona since I started visiting this part of the world. In 2018, fresh off two and a half months of bike touring in Japan, New Zealand, and Australia, Adam and I attempted to ride back home to Durango from Tucson. Within four days we called it quits on Christmas Day when we got caught in a blizzard in the Chiricahuas. Our friends Benedict and Nam graciously came to the rescue, transporting us to the nearest hot spring and then to the nearest town so we could rent a car and finish the journey back home. It was one of the best Christmases to date.

I didn't return to the Chiricahua cordillera until recently when I attempted the same route. This time, I was riding in the opposite direction from Las Cruces, New Mexico, back to the Appleton-Whittell Research Ranch in Elgin, Arizona. After pedaling two hundred miles in anticipation, I learned what all the fuss was about as I slowly approached the east side of the mountain range where a citadel of stone columns, spires, and hoodoos rose from the forest. Contrasted with the bleak, flat, and exposed desert of the vast San Simon Valley that I had just pedaled across, the Chiricahuas offered dense shade and a respite for my sunburn. They were also beaming with life; white-tailed deer, turkeys, javelina, and even running water after one of the driest monsoon seasons on record.

The Chiricahua Mountains’ namesake comes from the Indigenous People to the land. The Chiricahua Peoples battled to defend their territory from Spanish-Mexican settlers and armies for over two hundred years. However, after the Gadsden Purchase of 1854, they were ultimately and violently forced from their lands by the U.S. Army so that Euro-American settlers could colonize the West. The mountains themselves are located thirty-five-miles north of the southern border of the U.S. with Mexico, and on the eastern Arizona border with New Mexico. The main gravel road that travels across the range is seventeen miles long, split between a 2,700 ft climb and a 2,000 ft descent. This road is a rare high altitude gem through one of the largest of the Sky Islands of southern Arizona, reaching 8,000 ft (the highest peak in the Chiricahuas reaches 9,763 ft). A “sky Island” is one of many isolated mountain ranges in the Sonoran and Chihuahua deserts that produce multiple life zones with increased elevation. This phenomenon creates an island habitat for diverse flora and fauna surrounded by a desert sea.