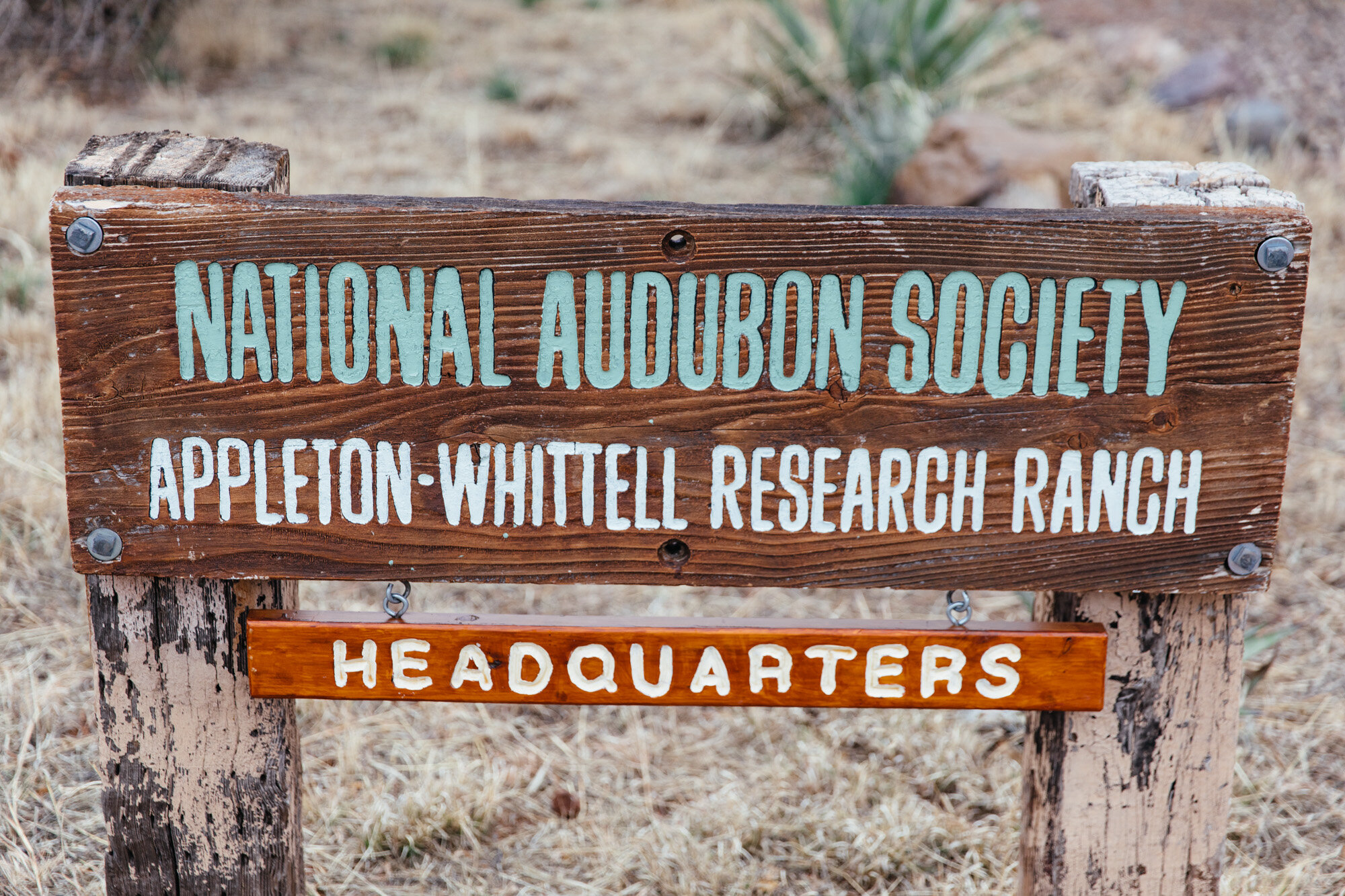

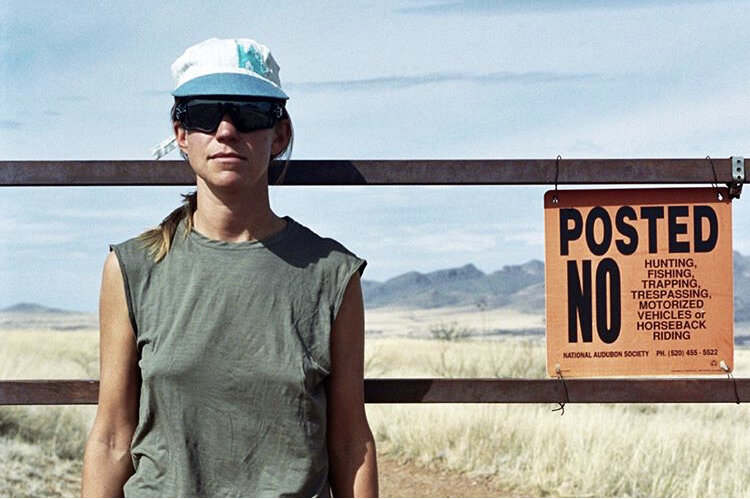

It's been over two months since Adam and I moved down to live at the 8,000 acre Appleton-Whittell Research Ranch (AWRR) 100 miles south of Tucson in Elgin, Arizona for the winter. For an introduction to the research ranch and what I am doing here, feel free to read my previous story about living at the AWRR.

On a bike tour the extent to which I typically go without seeing another person rarely exceeds three days. Scatter back-to-back three-day periods across three months, and you can get a good idea of how isolating it felt to ride the Trans America Dirt Road Trail, also known as the TAT. The 5,000-mile tour of the TAT back in 2015 was the most isolating experience I have had, until recently. Living on the AWRR during a pandemic has been an unexpected level of isolation I have ever known. This adjustment dominated what feels like the whole month of December. During this time Adam and I worked on getting the Swinging H ranch house, which is over one hundred years old, cleaned and fixed up into a more livable space for our five month stay. Because no one has lived in the Swinging H consistently for over twenty years, this project included getting it set up with hot water, internet, safe electricity, wood for heating, fewer cobwebs, less dust, and deterring mice and woodpeckers. We did all of this with the constant help and support of the ranch director and staff, Cristina, Ben, and Suzanne.

Contributing to the isolation of the research ranch's geographic location being 45 minutes from the closest grocery store and closed to visitors due to high Covid transmission rates in Santa Cruz County, is that there is minimal internet access. The only type of internet available at the research ranch is satellite internet, which requires sending radio signals to a satellite in space, which then beams the internet to the dish attached to the house. Most people have fiber or cable internet, which is typically instant and unlimited. Satellite internet is the new thing for folks who live in remote locations where cable and fiber is too expensive or impossible to install. For reasons beyond my understanding, satellite internet is limited to 100 Gb per month and delayed. Apparently, Elon Musk is working to improve the landscape for the future of satellite internet, but I am skeptical. Since moving here, Adam and I have taken a scrupulous approach to our data usage. We have cut out anything unnecessary to preserve what we have for video calls with friends and family, meetings, ten hours of zoom school per week, homework, and photo uploads.

Do you know what uses up a lot of unnecessary internet data? Instagram, Tiktok, and Netflix. I have largely stopped using these platforms during my stay here. I say largely because I will typically sneak a peek at the Tiktok videos my sisters send me. I'll also occasionally check my messages on Instagram via my web browser on my phone. Instagram is terrible to use through the web browser, but I use it because having the app is too easy and can quickly become an unconscious habit. As a recovering addict, I do not want to make it any easier to score my fix.

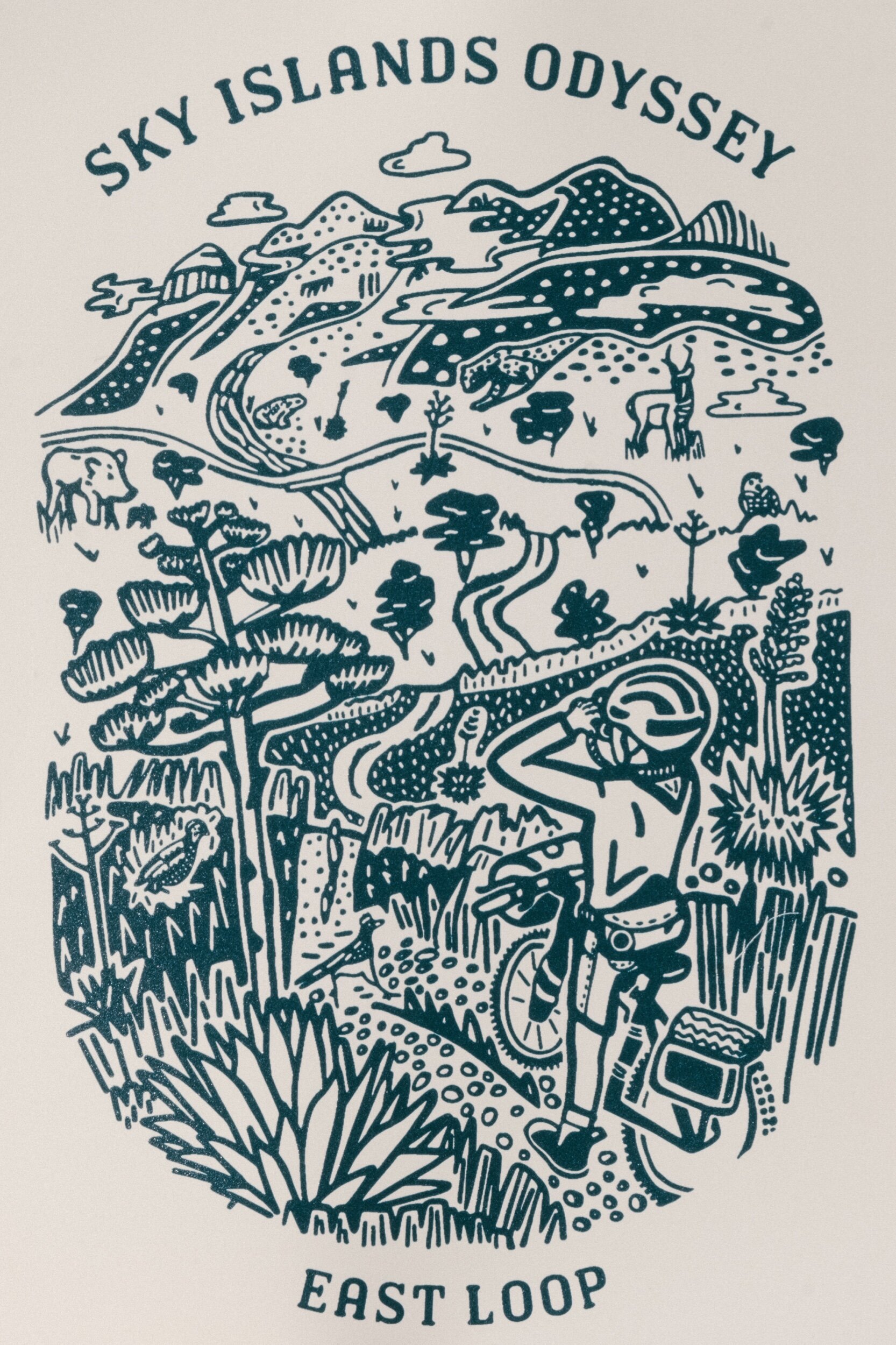

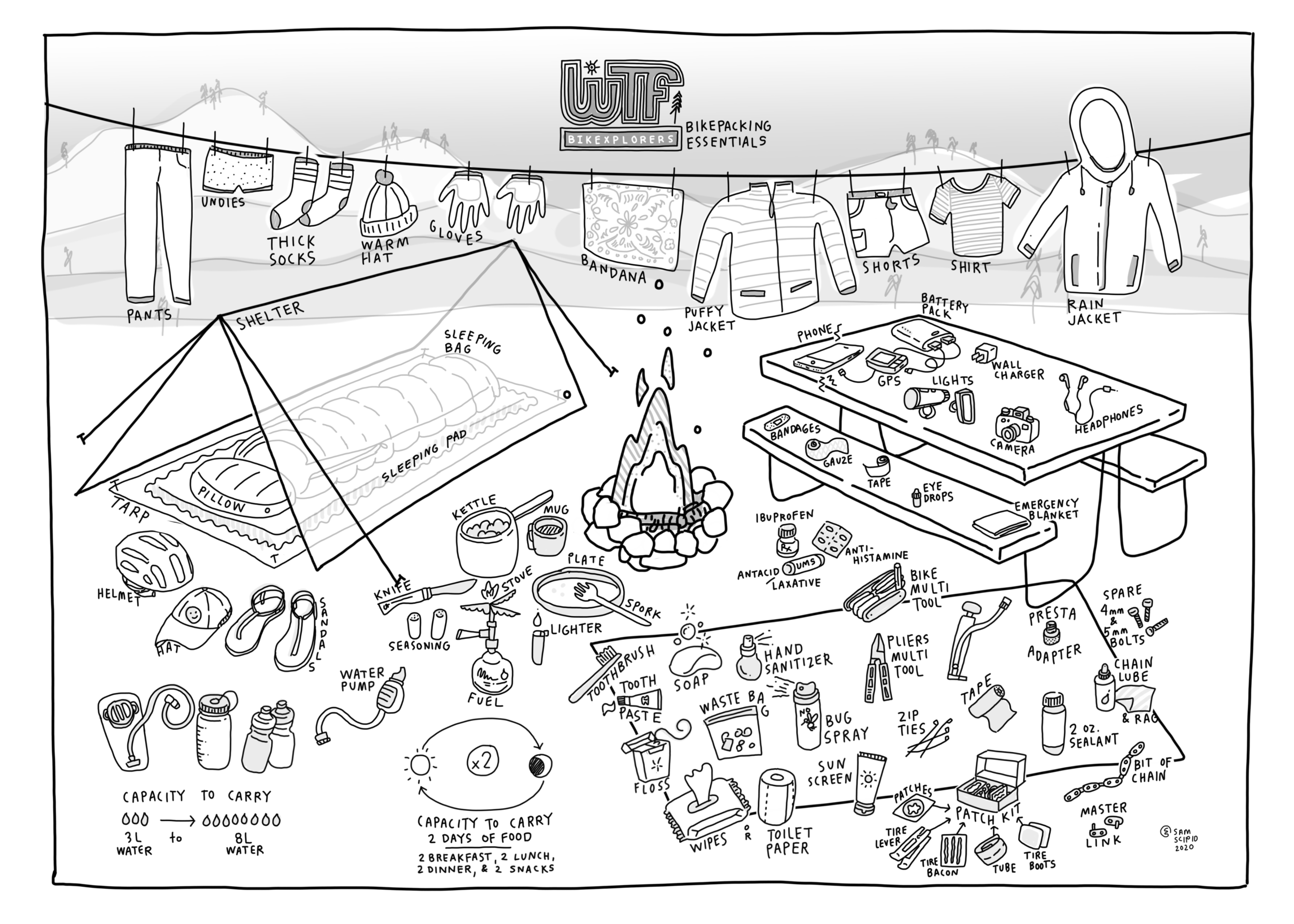

Overall, this detox feels like what I have needed for a long time. Whenever I feel lonely, I remind myself that Covid is mainly responsible for this, considering that the ranch would be open to regular bikepacking visitors riding the Sky Island Odyssey routes. I would also typically be preparing for Ruta del Jefe at the end of February, inevitably hosting a few gravel camps, as well as socializing with locals, fellow snowbirds, and whoever was in town visiting for the week. While I am certainly missing my friends this winter, in this social and streaming void, I have been embracing the space, time, curiosity, and interests that living on a research ranch inspires. Over the last couple of months I have had more time to ride, read, write, and cook; so much cooking, in fact, that I earned the nickname "Chef Fireball."

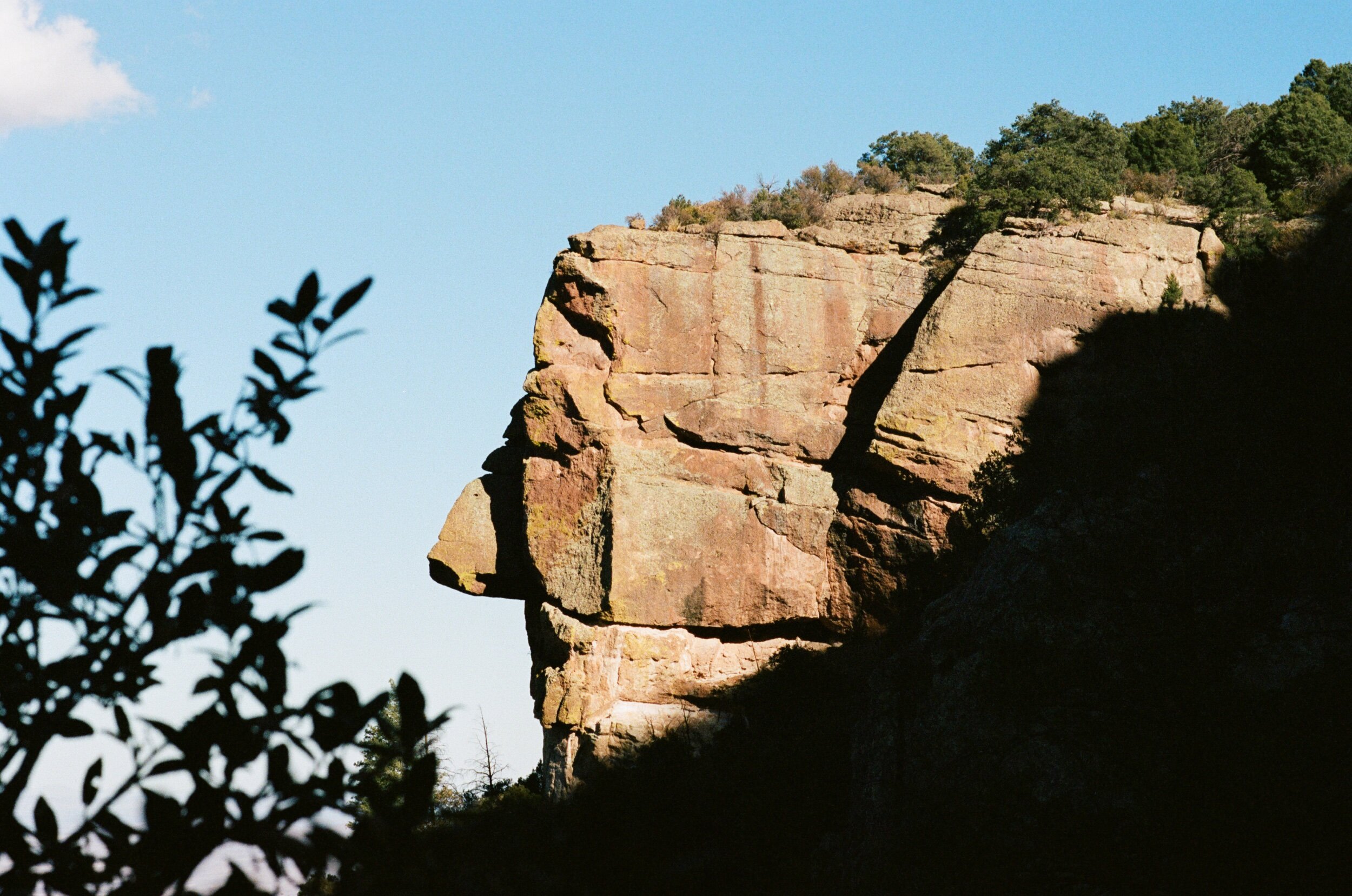

I have been riding my bike on and off the ranch, test riding zones I overlooked in the past. I am finding so much more than I anticipated and using this new information to update my current route offerings in the area and to develop some new ones. Despite its large and diverse road network, routing in this part of the world has never been easy due to nearly every base map being incorrect or outdated. I suppose the challenge is what makes it so fun and why I enjoy exploring down here so much.

I also have been reading about all the facets of the research ranch to inform my writing for some relatable and digestible educational signs and brochures for the average visitor. Thanks to contributions from former ranch directors Carl and Jane Bock and the University of Arizona Press, there is an abundance of literature written about the AWRR and the surrounding area. This library has provided me with an education of the history of the research ranch and livestock grazing in the Southwest; semi-arid grassland habitats; archeology of southeastern Arizona; and the endangered Chiricahua Leopard Frog. I am learning how humans have used land throughout history to our benefit and coming to terms with the impact that use has had on the land. Living on the research ranch, a semi-arid grassland not grazed by livestock in over fifty years, I can make these connections in a more personal way and see the positive effects of limiting human use first-hand. It seems that we humans are the invasive species spreading, choking out, and taking over native habitats for our greedy benefit.

Grasslands vs. Livestock Grazing

My time here has turned me into a grasslands snob, which is a blessing and a curse. When I ride off the ranch, I can't help but turn my nose up at some of the surrounding grasslands for how short and overgrazed they look or how many of them have been reduced to dirt and replaced with hoof prints and cow patties. This experience, coupled with my new knowledge, has led to an aha moment in understanding how detrimental the livestock grazing industry has been to the environment by eradicating biodiversity and beauty from natural landscapes and viable habitats for endangered species, specifically throughout the Southwest and Intermountain West. This information compounded with the knowledge that methane from the livestock industry contributes to 14.5 percent of the global greenhouse gas emissions has led me to cut meat out of my diet again. This time, however, not eating meat has been easier than it ever has been in the past.

The Christmas Bird Count

A highlight of the last couple of months was participating in the annual Christmas Bird Count, or CBC, where I spent an entire day moving slowly through the habitat within one or two miles of the Swinging H ranch house and recorded each bird species seen and their amount. Administered by the National Audubon Society, the CBC is a census of birds in the Western Hemisphere performed by volunteers. The count results provide population data for use in research and conservation biology but it also just so happens to be a fun recreational activity. I credit Aaron Van Geem, a friend and wildlife technician who joined us for the count, for making my first CBC an impactful and memorable experience. Aaron is trained and certified to track most animals in the western U.S. for conservation agencies and has worked specifically with jaguars, pygmy rabbits, bobcats, and Mexican spotted owls. What a job! While I have a good sense for spotting critters and Adam can identify different types of birds, Aaron was able to identify each specific species, including their gender and age. As a team of three, we allowed ourselves to fully geek out on birds from sunrise to sunset, at the end of which we were all thoroughly exhausted. This experience provided me with a greater appreciation of the biodiversity in this place where I get to live and cemented the species who also call it home into my memory.

Swinging H Ranch House

A few facts about the Swinging H ranch house; it was part of a separate ranch acquired by the Appleton family when they formed the Elgin Hereford Cattle Ranch over 20 years before selling their cattle to dedicate their land to be a research station in 1967. As we call it, the “H” is part of a lower compound of buildings on the research ranch about a mile from the headquarters, directors and conservation managers' residences and the barn. The area around the H includes a bunkhouse, casita, and a lab. It's nestled lower than most places on the ranch in O'Donnell Canyon at 4,700 ft, surrounded by rolling hills of grasslands and the occasional oak or sycamore tree. We heat this old house by schlepping thirty-to-forty-pounds of oak and mesquite into the house twice per day, splinters and all. The living room window inside the H offers a distractingly good view of the Mustang Mountains. The backyard, creatively landscaped with ocotillo, sotol, agave, prickly pair and blooming yucca, serves as a playscape for many neighborly birds: the Rufous and White-crowned sparrow, Canyon towhee, Lesser goldfinch, Curved-billed thrasher, Pyrrhuloxia, Loggerhead shrike, Roadrunner, and even an occasional visit from the local American Kestrel.

Wind

The weather of a semi-arid high grassland plain in the winter is a lot like living in Ohio in the sense that you can experience a 70-degree sunny day, 3" inches of snow and a tornado all in one week. A tornado is an exaggeration for southern Arizona, but the sentiment is the same when there are days where the near-constant winds increase 30-40 mph speeds. These days, the wind creates an eerie, unsettling howl through each gab of this old house. I typically hunker down inside, taking refuge from the intense conditions outside, and watch as the grasses blow as if they were waves in a stormy sea. Sometimes, I will venture out into the wind to get a break from the house and I am usually pleasantly surprised by how fine it is to ride through, primarily because of the massive tailwind for half the ride.

Time

Time feels like it is simultaneously flying by and not moving here. Part of me is overwhelmed by February already being here, and part of me feels like I have lived here for over a year. It is not uncommon for me to wear the same pair of wool-leggings for five-days straight. I am cherishing these moments with the expectation of a busy February with the ranch gradually opening back up to bikepackers; a tour on the Sky Islands Odyssey full loop for a film project with REI and Ford Motor Company; visits from a small cohort of friends from Austin, Texas; and my parents driving in from Ohio. Note: Adam and I are scheduled to quarantine and be tested before and after each of these visits to combat the spread of Covid.

My time at the research ranch will be coming to an end in April. In the meantime, I still have much I would like to see, learn, and do during the rest of this winter and making a list for winters to come.

Here is a list of some of the great books I have been reading during this time:

Amann, Andrew W. Jr. Bezy, John V. Ratkevich, Ron W. Witkind, Max. Ice Age Mammals of the San Pedro River Valley. Arizona Geological Survey, Tucson

Bahre, Conrad J. 1977. Land-Use History of the Research Ranch, Elgin, Arizona. Journal of the Arizona Academy of Science.

Basso, Keith H. Wisdom Sits In Places: Landscape and Language Among The Western Apache.

Bock, Carl E. Bock, Jane H. The View From Bald Hill: Thirty Years in an Arizona Grassland

Bock, Carl E. Bock, Jane H. Sonoita Plain: View from a Southwestern Grassland.

Sayre, Nathan F. Ranching, Endangered Species, and Urbanization in the Southwest. 2005. The University of Arizona Press